Abstract

Game-based art has implied and explicit

rules that artists expose and exploit for aesthetic and ideological

purposes. The thesis develops this theory of interactivity from

Noah Wardrip-Fruin's concept of playable media, Domini Lopes'

strongly interactive art, Eric Zimmerman's defined modes of interactivity,

and Ian Bogost's procedural rhetoric. The thesis explores the

aesthetic and ideological in games from Dadaism, Surrealism, Fluxus,

and contemporary artists Rafael Fajardo, Gabriel Orozco, Mary

Flanagan, Francisco Ortega-Grimaldo, Wafaa Bilal, Natalie Bookchin,

Voker Morawe, Timan Reiff, and Matthew Ritchie, and my own game-based

interactive works.

Introduction

Interactive art is an accepted but

contested art form. At issue for the artist, the critic, and the

observer is not a fundamental antagonism but a problematic definition.

Interactive art does not provoke public resistance or critical

opposition; it has its appeal, and adding the term interactive

to the description of a work can even make a work seem "more

sexy, more potent, [and] more creative." (1)

But the term does not necessarily deliver critical insight. Interactivity

is not opposed in the world of art; rather, it is under-defined

or perhaps misunderstood. When I encounter the term in the description

of a work, I want to ask, "What makes a work of art interactive?"

Definitions of interactivity do

exist, and I am not suggesting that the art form has not been

defined in helpful ways or that the contours of interactive art

have not been discussed. The contours of the art form have been

discussed at length and with considerable insight. Randi Hopkins

recognizes that interactive art calls for active engagement. She

says that "it is part of the very definition of interactive

art that we have to throw ourselves right into it—no armchair

appreciation or passive gazing allowed."(2)

The "Curatorial Mission Statement" of the Cambridge

non-profit space Art Interactive characterize the form as "contemporary,

experimental, and participatory" and says that those who

engage interactive art "play, create, and participate."(3)

It is, for many, active participation or the act of engagement

that defines the art form. But such a definition, though useful,

seems incomplete and even superficial. The definition recognizes

what people do with interactive art, but not necessarily how or

why they do it. There is something present that may or may not

be consciously observed that shapes acts of engagement and makes

art interactive.

What, then, makes art interactive?

The answer, in part, is code. Code defines the limitations of

environments and systems. The squares on a chessboard and the

keys on a keyboard provide good examples of coded physical limitations.

The coded environment of a Chess game is an eight by eight square

board that has two alternating colors; a standard computer keyboard

has one-hundred and four buttons, each bearing a unique symbol.

Physical limitations are part of the code of an interactive environment.

These codes may open an infinite number of possibilities for a

viewer; however, with the addition of rules, the possibilities

are narrowed, become finite, and lead to a specific end. Rules

govern players' interactions within the encoded environment,

and interactive art is rule-based.

This dimension of interactivity

is most evident in games. A traditional board game, for example,

has rules; the rules are stated explicitly, and those who play

the game must follow the rules or break them. The rules of Chess

and the rules of Checkers determine how players use the

eight by eight square matrix. Likewise, video games have rules,

though video-game rules are more complex. Video games are programmed

games with written instructions that govern the players' actions

and coded instructions that control hardware inputs and digital

outputs. Strongly interactive or process-oriented works "have

internally-defined procedures that allow them to respond to their

audiences, recombine their elements, and transform in ways that

result in many different possibilities."(4)

Playing a game or engaging any interactive work changes the possibilities

and the player's immediate experience of the game. It is the interactivity

itself that effects the state of play, and during the play, the

observer and the work respond, recombine, and transform. This

does not occur in fixed media such as painting, but it is a defining

aspect of interactive media. In interactive art, the observer

and the work are constructed by rules that can be bent or broken,

but cannot be absent. Whether implicit or explicit, there will

always be rules that govern the acts of engagement of works of

art.

|

| Argument gallery

Tag | Players are encouraged to play |

|

|

Engagement,

of course, is physical and sensory, for engagement activates

visual, aural, or tactile contacts with the work and yields

cognitive, emotive, and physiological responses. The observer

senses and manipulates the art, and in turn thinks, feels,

and reacts. Any sensing and manipulating, however, will

be guided by codes and rules. The codes and rules can be

unique to the piece, and they can, with certain limitations,

be selected, modified, and manipulated by those who create,

engage, and display the art. Changing the rules of the game

or the rules of engagement may be complicated, or it may

be as simple as changing the signage in an exhibit. The

sign that warns, "DO NOT TOUCH," and the invitation,

"PLEASE TOUCH," illustrate the point. These signs

establish rules and, at the discretion of the artist or

museum, can be modified. Changing a sign, changes the rules

of engagement, and this changes the observer's experience

and response. The rules of engagement define the form of

the interactivity. The art work's rules guide responses;

they trigger memories, emotions, and analysis, and the artist

can manipulate these rules for aesthetic and persuasive

purposes.

|

Objective

My objective is to define a mode

of interactive art that exposes and exploits implicit and explicit

rules of engagement. The thesis has three sections. In the first

section, which describes a theoretical framework, I will draw

upon the work of Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Dominic Lopes to explore

the operation of rules in games and interactivity, and I will

discuss how rules may be exposed and exploited to serve aesthetic

and ideological ends. I will also consider the theoretical paradigms

of Eric Zimmerman and Ian Bogost. In the second section, I will

discuss historical precedents for my work in Duchamp's relationship

to the Dadaist movement and his interest in Chess, early Surrealist

games, the games of the Fluxus movement and Yoko Ono in particular,

and the contemporary game artists Rafael Fajardo, Gabriel Orozco,

Mary Flanagan, and Francisco Ortega-Grimaldo, among others. In

the third section, I will relate theory and history to my work

as a new media artist.

Motivation

Rule-based art can be used for aesthetic

ends and for social criticism, and I am motivated by both concerns.

I am interested in rules at work within the art and in society,

especially but not exclusively, rules that sustain violence. My

motive in creating interactive art is to expose overlooked behaviors

and to encourage a fresh questioning of social habits and values.

Some, I fear, do not see habits and practices that perpetuate

injustice, and others see but ignore them. My intent is to expose,

and my work is a form of social activism. It is not, however,

overt activism like marching in protest or signing a petition.

It is a covert protest that does not carry a banner down a street

but makes a statement from an online exhibit or gallery. I do

not intend to force attention but to invite reflection through

playful engagement and interactivity. My work affords viewers

an opportunity to discover from a safe distance something about

the dynamic and destructive operation of violence, without suffering

violence, and I use playful games to expose life's larger

and more dangerous ones. I want people to make these discoveries

on their own through interactive experiences and ultimately to

avoid and shun social violence.

I create game-based art to engage

and to change viewers, to alter perspectives, though I cannot

predict the effect. People tend to overlook or resist new or contrary

ideas, but interactive art can subvert resistance by being playful,

entertaining and ironic. When viewers engage certain kinds of

game-based art, they enter into a dialogue with the artwork and

within themselves. They may want to play a game that challenges

their skills, but I want to challenge their perceptions of the

world. In the book, What Video Games Have to Teach Us About

Learning and Literacy, Paul Gee explores the paradox that

children and adults who may avoid formal study, eagerly learn

how to play video games on their own without online or classroom

instruction. (5) They like

to play games, so they learn how. Marc Prensky also explores the

paradox in his work, Digital Game-Based Learning. (6)

I am not seeking a new form of pedagogy in interactive art; rather,

I want to use the expressive aspects of interactivity, and Gee's

and Prensky's explorations show the importance of games

and their ability to capture attention and to communicate ideas.

According to Michel Foucault, rules

and discipline regulate individual behavior and the social body.

People play by the rules of their social group, and the rules

are largely social constructs, taught and learned behaviors. Sets

of rules reveal something about the societies that create, observe,

and transmit them, yet the rules are not always acknowledged.

They may be real, but they may not be obvious or recognized. From

Foucault's perspective, power works best when its mechanism's

are hidden. The creation of art that explicitly employs rules

(game-based art) or that exposes the rules that are at work in

a social group, is a form of activism that reveals and empowers.

My game-based art exposes rules at work in violent conflict.

What, then, is my rationale for

using games and creating game-based art to express ideas? In part,

I want to express resistance-prone ideas in resistance-diminishing

games. Players will learn how to play an interesting game and,

through the process, will learn more than just how to play the

game. I want players to understand something about society. Game-based

art invites and sustains reflection; the interactions require

active, rather than passive engagement, and engagement fosters

learning. For this reason—as artist and activist—I

am drawn to the game and game-based art.�

I. Theory

Game-based art is part of a continuum

of static, reactive, and interactive art. In static art, an observer

responds to an object; in reactive art, an object responds to

an observer; in game-based art, observer and object respond to

one another. Game-based art is strongly interactive, and this

mode of art recognizes that there is a stated or assumed etiquette

and protocol to interactivity.(7)

Interactivity entails a constrained give-and-take between the

art and the observer. The user must "play the game."

This distinguishes game-based art from other forms, for engagement

requires rule-based participation and operates within a coded

environment; there is a framed relationship between the observer

and the observed, between the inter-active art and the inter-actor,

though this could be said of all art.(8)

The boundaries for game-based art are not rigid frames, of course,

but rather encompass a framework of explicit and implied rules.

A coded environment and a set of rules define and govern engagement

with the art, and because the rules of games and the rules of

art are rooted in social matrices, conventions, perceptions, and

ideals, game-based art tends to be activist art. Interactivity

is inherently activist, for in both realms people must get involved.

In my work, I am exposing rules of engagement to reveal social

issues and to provoke cultural awareness and critique.

Encoded Environments

|

| Screen shot from

The McDonald's Video Game | Molleindustria |

|

|

Game-based art, one may reasonably assume, invites a measure

of reflection on life's games. Francisco Ortega-Grimaldo's

game, Observance, reflects the game of cat-and-mouse that

immigrants and border guards "play" in trying to

gain or to bar entrance to a country. Playing the game provokes

reflection on the realities of border politics. Molleindustria's

The McDonald's Videogame recalls the dynamics of

business and the lure of profiteering, for the object of the

game, like the object of corporate life, is to make the most

money at the lowest possible cost. Board games such as The

Game of Life and Monopoly are transparent examples

of art imitating life, the structured relationships, expectations,

and obligations that order life within society. The game titles

themselves suggest a connection between the games that are

played and a game that is lived. |

| In the game of Monopoly, the player

assumes the role of an investor who uses money to acquire

deeds to properties and to accumulate wealth. The game is

all about business. In the game, however, there is no real

property. The players move small game pieces around a board,

the money and property of the game are fake, and the role

of property tycoon is imaginary, but money and property and

business do exist in the social worlds of the game's players

and the game's maker, and their social worlds overlap. The

overlap is not simply two dimensional, since three worlds

collide: the worlds of the game, the game's creators, and

the game's players, who may change over time. Monopoly

originated in the America of the Great Depression, and the

social world of the 1930s established the rules of the game,

but the social world of a player in 2008 generates a different

perception of the game.(9)

Contemporary revisions of Monopoly (e.g., the Star

Wars and Here and Now editions) are one evidence of the complex

intersection of the three worlds of game play, and the intersection

of game, provenance, and player continue to evolve with technological

innovations, the impact of new media, and social changes.(10) |

|

|

| Monopoly: Here and

Now Edition | Hasbro |

|

|

|

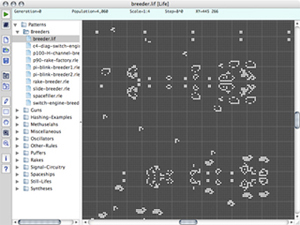

above:Game

of Life | Milton Bradley. below:Golly | Andrew Trevorrow

and Tomas Rokicki

|

|

|

Milton Bradley's multiple-player game, The

Game of Life, Conway's single-player game, Life, and

life itself have distinct rules and codes. The rules in Milton

Bradley's games are printed in the lid of the box and are

clearly defined and idealist: to attain a successful life,

one must go to school, get married, find a job, raise kids,

and retire—all from the seat of a tiny plastic automobile.

Player's navigate the world of the game by spinning a wheel

of fortune and by moving a tiny plastic automobile on a colorful

printed roadway. Spins and moves effect the course of the

player's life. They are, in fact, the player's life within

the game and in an idealized world envisioned by the game's

creators. That world and the game are utopian, for death is

not an aspect of Milton Bradley's Game of Life. Conway's

Life, on the other hand, is not utopian and has a

"genetic" code that encompasses birth, survival,

and death.(11) The player

first creates a pattern of blocks on a checkerboard, and then

Life's code plays out to the end, either in patterns laid

out by players manually on the board or automatically on a

computer screen. Depending on the pattern, life continues,

reaches stasis, or perishes. Golly, a computer adaptation

of Conway's Life, has the code but few rules to guide

player interaction; the rules do not need to be known because

the computer is programmed to play the game to its conclusion.(12)

Players are free to create any initial pattern of cells, but

once the pattern is entered, it takes on a life of its own

and grows, changes, and either survives or dies in an "unbounded

universe." In Golly, the computer applies the

rules in an encoded environment, but interactivity is minimal;

the player moves only once, then watches. |

Games reflect ideals and simulate

realities, and the encoded environments of the game, its creators,

and its players have rules that intersect. The intersection of

these worlds is a locus of interactivity that artists and players

can experience, observe, engage, and exploit, though some modes

of interactivity are more promising than others.

Modes of Interactivity

In an article entitled, "Narrative,

Interactivity, Play and Games: Four Naughty Concepts in Need of

Discipline," Eric Zimmerman discusses four modes of interactivity:

cognitive, functional, explicit, and meta.(13)

The first mode, cognitive interactivity, involves interpretive

participation: the observer reads a text, observes an object,

or hears a sound, and reacts intellectually, emotionally, and

psychologically. In this mode, virtually any engagement can be

deemed interactive. The second mode, functional interactivity,

is utilitarian and relates to the material nature of the piece:

how a person experiences its design, texture, and operation, and

how one navigates from one point to another within the work. The

third mode, explicit interactivity, entails an immediate or direct

contribution to the design, operation, and procedures of the work.

Explicit interaction is overt participation: clicking hypertext

links, pulling a joystick trigger, following rules, or moving

objects. Most importantly, the participant makes choices in this

mode of interaction, and the choices effect and can be effected

by random or programmed events. The fourth mode, meta-interactivity

or cultural participation, the viewer's experience extends outside

the original work to its appropriation, promotion, subversion,

or deconstruction. The new media artist can create interactive

works that exploit the potency of any of these modes or all of

them in combination, but the aesthetic and activist potential

of each varies.

"Making and appreciating art,"

according to Dominic Lopes, "are always interactive activities,"

and this complicates notions of interactive art.(14)

As an artist working in new media, I am intrigued by the complications.

Lopes categorizes art as weakly or strongly interactive. Art that

is weakly interactive allows users to explore the content of the

artwork in various sequences or to experience only a part of the

work. In strongly interactive media, users experience the work

as a whole, and each exploration determines the state of the work

and the experience of the user. For Lopes, the paradigm for interactivity

is the game, and a game is strongly interactive because "the

course of the game depends on the players' choices."(15)

Likewise, in strongly interactive art, the properties of the work

are determined by the user's actions.

Noah Wardrip-Fruin also sees similarities

between interactive art and interactive games, but finds it more

useful to discuss qualities of interactivity than categories.(16)

In describing his experiments with textual instruments, "interactive"

serves as an "accurate, but overly broad" term, and

"game" is too narrow. He does not distinguish interactive

games and interactive art but recognizes ambiguity and continuity

and applies the term "playable media" to "things

that we play (and create to play) but that are arguably not games."

Instead of asking, "Is this a game?" Wardrip-Fruin asks,

"How is this played?" He pursues art that invites and

structures play.

In "Art Games: Interactivity

and the Embodied Gaze," Graham and Elizabeth Coulter-Smith

explore traditional and performative interaction in contemporary

new media art. Like Lopes and Wardrip-Fruin, the Coulter-Smiths

see a shift in the viewer's relationship to new media. They describe

the traditional role of the viewer as "looking and respectfully

appreciating" and refer to this "mode of interaction

as 'reading.'"(17) The

reading gaze in traditional fine art is "distanced"

and "disembodied," and the status of artist (as genius)

and artwork (as precious) alienates and is an obstacle to interaction.(18)

Art that limits itself to "reading" but not "writing"

is, on my continuum, static; art is static when the observer responds

to the art, reactive when the art responds to the observer, and

interactive when art and observer respond to one another. Interactive

art is, so to speak, "written" as well as "read."

Interactive art is what one does, not merely what one sees. Game-based

art reifies experience. The participant engages the work and in

turn is engaged by the work. The game is art, with all the potential

of art. The Coulter-Smiths write, "The notion of a creative

game that can interpenetrate everyday life leads us to the concept

of serious play."(19)

The playfulness of the art is meaningful. It is also available.

They conclude that "the creative game is potentially a powerful

strategy that will enable deconstructive art to escape its current

assimilation into the traditional values of the precious work

of art and the apotheosis of the artist as genius." Interactivity

makes the viewer a genius, too, because the viewer activates and

creates the art. Art games can also eschew the notion of "genius"

altogether. The interactivity of the game-based art is paradigmatic,

and the paradigm can be exploited.

Exposing and Exploiting

Rules

Game-based art is ruled-based, and

the rules can be exposed and exploited by the artist. To play

a game, a player, of course, must follow a set of rules, and the

rules always have real-world analogs. War, for example, has been

waged on real battlefields throughout history, and it is played

on game boards on kitchen tables. The board game is understood

because its analog is known. The artist can exploit the analogy

in several ways. The artist can borrow or build upon what is known

(e.g., about war and warfare, military personnel and chain of

command, weaponry and tactics, geography and history). Or, the

artist can expand or challenge what is known (e.g., historical

defeats as well as victories, collateral damages, political and

humanitarian costs). The rules can be borrowed, bent, or broken

for aesthetic or activist purpose.

Game-based art is rhetorical. In

the book, Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Video

Games, Ian Bogost proposes that games have a procedural rhetoric

that develops an argument. In a video game, the rhetoric is visual

as well as verbal, and the rhetoric logically encompasses aural

and tactile cues. The argument unfolds through the process of

playing the game, and the very rules that define the game also

shape the argument. Bogost states that "procedural rhetoric

is the practice of using processes persuasively, just as verbal

rhetoric is the practice of using oratory persuasively and visual

rhetoric is the practice of using images persuasively."(20)

Bogost uses Molleindustria's The McDonald's Videogame

to illustrate the point. The video game exposes some of the business

practices of the fast-food giant. The player controls four aspects

of a simulated McDonald's enterprise that need to be managed simultaneously:

the third-world pasture, the slaughter house, the restaurant,

and the corporate offices. In each of the four aspects, players

must not only make difficult business decisions but moral choices

as well. The player may use varying tactics—including bribery

of government officials, bulldozing rain-forest, and use of growth

hormones—to achieve the goal of making the highest profit.

Unsavory tactics, however, will provoke consumer complaints and

lead to health safety violations that only lobbying and public

relations campaigns by the corporate offices can "fix."

By playing the game, one encounters the argument that it is impossible

to make a 99¢ hamburger and turn a profit without adverse

impact on society and the environment.

The rules of a game guide the players,

and playing creates the argument. The rules generate the rhetoric.

The rhetoric of a game need not defend or attack a position or

institution, though it certainly can. The rhetoric can simply

inform (though bias is always operative). Observers play the game

and in doing so discover something they may have missed, and learn

about the rules of life by experiencing a microcosm. The microcosm

reveals the macrocosm and becomes a map. As Matthew Ritchie asks,

"Maybe the rules are just another way of asking what will

happen next?"(21) With

game-based art, as I envision it, the rules are essential to the

art, and the artist can make, borrow, bend, or break the rules

of the game. Which game? The game that is being created and will

be played, but also the realities that are being exposed (i.e.,

the game of life itself). Art at its best exposes, and the rhetorical

power of games and new media lend seriousness to play and imply

that games are indeed art.

With the rise of the digital revolution,

increasing attention has been given to video games, art, and the

relationship between the two. The revolution has stimulated debate

over the question, "Can a video game be art?" Manifestos

and calls for better and more serious games have even rekindled

interest in an eight-bit aesthetic typically associated with early

video games of the 1980s as mice, keyboards, and code have supplanted

card and board games.

| Ernest Adams challenges game makers to

create better and more innovative games in his "Dogma

2001: A Challenge to Game Designers."(22)

He advises designers to break the standard game mold by avoiding

cliché tricks such as bullet time, power-ups, and predictable

characters (e.g., elves, knights, Nazis, vampires, and mutants).

Adams forbids common game types (e.g. first-person shooters,

role-playing, jump-and-shoot side scrollers), as well as a

reliance on hardware and other input devices. Victory and

defeat, winning and losing remain important, but in his approach,

there cannot be good versus evil. Many of Adams's rules could

be adopted by artists and designers, and game players would

benefit. As a designer, I would follow all ten of his rules;

however, as an artist, I would ignore some.(23)

First, I would not limit the type of game, for this limits

modes of expression and means for commentary. By subverting

violent first-person shooters, side-scrollers, and RPGs, artists

are able to exploit familiar control systems and to bend rules.

Making the guns shoot paint instead of bullets creates new

challenges for players and would shift the goals of the game

from killing to less violent and more constructive actions.

For example, Cory Arcangel's I

Shot Andy Warhol, a hacked Nintendo game originally

titled Hogans Alley, removes characters of gun-toting

bad guys and replaces them with the Pope, Flava Flav, Colonel

Sanders, and Andy Warhol.(24)

Feng Membo's Q4U and AH_Q exploit the first-person

shooter genre through manipulation of the graphics. In Q4U

and AH_Q, Membo becomes the main character in the

computer game, DOOM.(25)

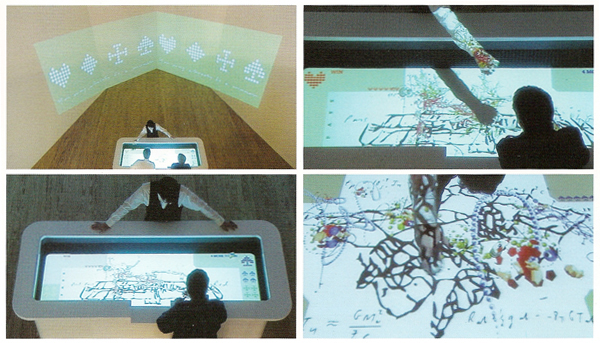

Second, hardware should remain a very important factor in

art games. The hardware is a crucial element that can enhance

the interaction of the game. Hardware can enable players to

use their whole bodies and to move within physical space to

control avatars in virtual space, or it can confine them to

a small intimate space of a board or table game. Art games

are generally not designed for mass-consumption, so they should

not be designed for the lowest common denominator as some

commercial games are—unless, of course, doing so adds

necessary context to the artwork. Input devices should also

be well considered. Are mice and keyboards the appropriate

mode of interaction for a game about collaboration? Mary

Flanagan's giant Atari joystick requires two people to

move each axis of the joystick and one more to push the button,

the interface forces collaboration. Mice and keyboards do

not have the same presence nor do they invite more than one

user at a time. Maintaining or bending hardware rules will

also change the rhetoric of the game. |

|

|

| I Shot Andy Warhol

| Cory Arcangel | 2002 |

|

Nic Kelman's "Video Game Arts Manifesto" calls for the

development of games that are not merely entertainment. He pushes

for emotional involvement that is not just thrills and excitement,

and he insists on better visual design and writing. Like Adams,

Kelman calls for unique and original visuals instead of reliance

on other established styles, such as, "graffiti, anime and

French comic books." (26)

Francisco Ortega-Grimaldo advocates

the Ludoztli

Movement, which uses board games as art and social commentary.

Ortega-Grimaldo's urges "artists to stop making non-interactive

art, and break the wall between the art object and passive viewer."

He hopes that participation in the movement, through the interaction

with artful games as well as with fellow participants, that players

will experience changes of heart and will develop new perceptions

of their worlds. Ortega-Grimaldo concludes that it is through

games that the viewer actively engages a social statement, injustice,

or opinion, and plays ideas out.

The challenges, manifestos, and

movements discussed above advocate similar goals for the creator/artist

and viewer/player: namely, that together they create moving works

of art.�

II. Historical Precedents

Play captivated artists late in

the twentieth century. The game became a topic of discussion,

an example in theory, and an object of art. In an article entitled,

"Cold War Games and Postwar Art," Claudia Mesch notes

that "late twentieth-century artists consistently turned

to the game as structure or subject for their art."(27)

They explored theoretical and practical issues that continue to

be relevant in new media art, and their game-related art provides

a context for my own work.

Duchamp, Dada and Chess

|

| End Game | Dorothea

Tanning | 1944 | Collection of Harold and Gertrud

Parker, Tiburon, California |

|

|

A game of particular significance in late

twentieth-century art is the game of Chess, which

more than a few artists appropriated in their work. Larry

List, who curated "The Imagery of Chess Revisited,"

a recreation of "the groundbreaking 1944 exhibition organized

by Marcel Duchamp and Max Ernst at the Julien Levy Gallery,"(28)

writes, "In a time of world conflict when many looked

on helplessly, Chess represented a controllable,

tabletop form of ritual warfare, devoid of chance and predicated

totally on skill."(29)

The artists of the era "mined the rich associations of

the game and its history."(30)

They explored the form and function of set designs and created

works that employed Chess as a metaphor of conflict

and conquest. The Modernists generally simplified the pieces

to geometric forms expressing movement and function, as did

the designers from the Bauhaus school. The Surrealist André

Breton filled glasses with varying amounts of red or white

wine to differentiate pieces and their functions. The pieces

and board also inspired paintings such as Dorothea Tanning's

End Game in which a white, satin, high-heeled shoe

violently crushes a bishop's miter.(31) |

| Concerning Duchamp, List writes, "While

his peers were beginning to veil the subject matter in their

art, Duchamp was veiling the fact that he was making art at

all, by camouflaging it as chess." (32)

Duchamp, it is fair to say, was consumed by Chess.

It was an escape that allowed him "to live in a universe

where symbolic equivalents replaced objects instead of referring

to them," a world that can be seen as the polar opposite

of the Dadaist tradition for which he is famous.(33)

As a Dadaist, Duchamp achieved great success by creatively

breaking and bending the rules of the art world; yet he had

equivalent success as a competitive Chess player,

creatively following the rules of the game. Jerrold Seigel

points out the irony of Duchamp's approach to the worlds of

art and Chess: "one might notice first of all

that unlike art–at least modern art – [Chess]

is a realm where the rules never change."(34) |

|

|

| Duchamp Playing Chess

with Eva Babitz | Photo by Julian Wesser | 1963 |

|

|

| Pocket Chess |

Marcel Duchamp | 1943 | Archives Marcel Duchamp, France |

|

|

Duchamp played Chess by the rules

but also modified the board and pieces in interesting ways.

Duchamp's Pocket Chess was a modification of a commercially

available Chess set. He replaced the celluloid pieces with

ones of his own design, adding pins to the board. The new

pieces rested on the pins, which prevented them from slipping

across its tiny surface. The modification, however, made the

game more difficult to play and made it more of an art object

than a playable game. |

It is well known that Duchamp sought

to abandon retinal art in favor of an art that would challenge

and engage the mind of the viewer. Seigel suggests that "for

Duchamp, playing chess was one more way to paint a portrait of

himself as a man and artist."(35)

I believe that he found the level of engagement he sought not

in art that was static and simply viewed, but in the activity

of playing a game of Chess.

Surrealist

| André Breton once characterized

the whole of Surrealism as a "persistent playing of games."(36)

But the games that the Surrealists played were not art; rather,

the games were used to create art. Surrealist games were tools

of automatism, a technique for spontaneously writing or drawing

without aesthetic or moral censorship. When played by the

rules, the games allowed a group of artists to act as one,

without the dominating influence of a single ego. For example,

the Exquisite Corpse (Cadavres exquis),

a game developed in 1925, is a collaborative procedure of

collecting and assembling words or images to compose one work

devoid of any one individual's control over the participants.

Players added sentences to a composition by following rules,

or they added images based on seeing the end of what the previous

player had contributed.(37)

The Surrealist Inquiries were question-and-answer

games published regularly in various periodicals such as Littérature

and La Révolution Surréaliste. These

were designed to be unexpected and to reveal unsuspected and

perhaps fundamental information about the respondents. The

questioner might ask, "Suicide: is it a solution?"

If respondents considered the question a moral one, they would

often fall under editorial abuse.(38)

These types of surrealist games pushed inquiry almost to levels

of inquisition, at times making them uncomfortable experiences.(39)

Although the rules worked, and the artworks produced are unique,

the artists were not able to control or predict what the final

piece would say, or how it would be interpreted by players

beyond an exploration into the sub-conscience. The games were

designed to shed light on the inner, unacknowledged working

of the human mind. The rules facilitated a letting go, a releasing

of control; they let interpretation and chance uncover hidden

truths. |

|

|

| Wine Glass Chess

Set and Board | André Brenton & Nicolas Calas

| 2004 Replica of lost 1944 original |

|

Fluxus

|

| Play it by Trust

| Yoko Ono | 1966-1998 |

|

|

According

to Mesch, "Fluxus always cultivated the qualities of

play, which [George] Maciunas understood as being connected

to the mass-culture phenomena of amusement and entertainment

within art."(40)

Fluxus games such as Chess on a Backgammon table

were, of course, unplayable, but this did not make the works

failures. They were artistic expressions and succeeded in

making players and observers think about the nature of rules.

To play Chess on a Backgammon table is to play

neither Chess nor Backgammon, for the

rules must be modified in a hybrid of the two games. Fluxus

games were not gags; they were commentaries on the rules

of making, buying, selling, and canonizing art. Through

entertainment and "lack of seriousness," they

were able to grab the public's attention, with the hope

that Fluxus works "might bring the public to the realization

of social and political injustice."(41)

|

| Yoko Ono's Play it by Trust consisted

of a series of installations based on the concept of an all

white Chess set. The installations vary in form.

In East Hampton, New York, at Longhouse, Ono installed a 16.5

foot square marble and concrete Chess set. There

have been a number of small white table and chair sets produced,

and an iteration of ten all white sets laid out at a conference

table. Ono's Chess modifications represent prime

examples of a game—specifically a war game—adapted

and utilized as a call for peace. In Play it by Trust,

players ultimately lose track of their pieces as their forces

move forward. The pieces become lost as "enemies"

meet, and, unable to differentiate sides by color, players

either must remember where their pieces are, remember the

direction their pieces face, or realize that they are all

the same. The experience of becoming lost ultimately shows

that both sides are equal, forcing players either to follow

the standard rules for Chess or to create a new way

to play. Here a game that traditionally represents a war is

used to show that there are alternatives to fighting, and

that when people recognize their similarities, they can find

new ways to play, work together, and coexist in peace. |

|

|

| Play it by Trust

| Yoko Ono | 1999 |

|

Contemporary Artists

|

| Virtual Jihadi

screen shot | Wafaa Bilal | 2008 |

|

|

Wafaa

Bilal is an Iraqi born American artist whose

work met with much controversy in March 2008. Bilal's Virtual

Jihadi is a game modification once removed. To explain what

I mean by "once removed," I must trace the lineage

of the original game and its first modification. In 2002,

Petrilla Entertainment had released the game, Quest

for Al-Qa'eda: The Hunt for Bin Laden. In 2003 Petrilla

released Quest

for Saddam, a first-person shooter in which the

player hunts down and kills Saddam Hussein. The Quest

for Saddam game was marketed online and even promoted

on Fox News, CNN, MSNBC and Tech TV. In 2006, CNN reported

that SITE (Search for International Terrorist Entities),

"a jihadist mouthpiece organization," had created

Quest for Bush: The Night of Bush Capturing, which

was based on Quest for Al-Qa'eda, and they used

the code from Quest for Saddam. In this game, however,

players battled against armies of characters that look like

George W. Bush.(42) Quest

for Bush was a modification of Quest for Saddam.

Virtual Jihadi is a modification of Quest for

Bush, in which Bilal uses the same game code but changes

the skin of the protagonist to look like himself (much like

Feng Membo does in Q4U). Bilal's modification of

the game is intended to illustrate the plight of Iraqis

today. The game begins with the protagonist allied with

American forces; as the game progresses, their allegiance

shifts to Al-Qa'eda. The shift is not made for

ideological reasons, but as a means of survival. To quote

Bilal's statement about the work, "In these difficult

times, when we are at war with another nation, it is our

duty as artists and citizens to improvise strategies of

engagement for dialogue."(43)

One may agree with what Bilal is saying about the need for

dialogue and with what he is saying with his art, and yet

recognize that his work is controversial and will continue

to face challenges. One challenge is censorship. The work

is shocking, yet those who may need to understand the message

of the work may protest the work and refuse to engage it.

Some may condemn the work without knowing the work or its

context.

|

|

| The Intruder | Natalie

Bookchin | 1999-2000 |

Natalie Bookchin's The

Intruder is an internet adaptation of a short love story

by Jorge Luis Borges.(44) The

story is brutal and tragic, and Bookchin makes it into a game,

albeit a serious game. Over a course of ten distinct levels, Bookchin

uses differing 70's and early 80's video-game interfaces as metaphors

for "shooting, wounding and surveying (a woman's body),"

and she makes the metaphors "grossly apparent."(45)

As players work through each level, they are rewarded with pieces

of the Borges narrative instead of points. To confuse and implicate

a player, Bookchin will shift the player's position throughout

the game. A player will shift to opposing sides, will assume the

roll of a male and then a female character. Players also learn

that in some levels, they must lose to proceed. This makes the

player an accomplice in the tragic murder of a woman. If players

choose to proceed, then the woman dies; if they do not, they are

not able to see the full story.

| Rafael Fajardo, a contemporary

artist and founder of the collaborative SWEAT,

has worked on socially conscious video games related to U.S./Mexico

border and immigration issues. The collaborative's first game,

Crosser, was completed in 2000 and is modeled after

the arcade game, Frogger, a game about frogs crossing

a busy street. In Crosser, the player helps Juan

cross the U.S./Mexico border. Fajardo adjusted the controls

of the game to make the game more difficult than Frogger.

For example, using the controls to take one step forward might

mean taking two steps backward, illustrating the challenges

that immigrants experience when trying to cross the border.

Mobility is limited by re-calibrated game controllers, and

players encounter obstacles such as a polluted Rio Grand River

and border guards who patrol on foot, in SUVs, and in helicopters. |

|

|

| Crosser screen shots

| Rafael Fajardo | 2000 |

|

|

| [Giantjoystick] | Mary Flanagan

| 2006 |

|

|

Mary

Flanagan's 2006 [Giantjoystick]

is a ten-foot tall game controller that is modeled after

the classic 1977 Atari model 2600 joystick. Flanagan wanted

to create a collaborative interface, and she did this by

increasing the controller's dimensions. To use the joystick

to play one of the classic Atari games, players have to

work together. The joystick is so large that two people

must move the stick back and forth and a third must push

the fire button. It is simply impossible to play the game

by oneself. Although the joystick is used to play traditional

Atari games, Flanagan states that "it is not a software

art piece but a collaborative social sculpture."(46)

The work is nostalgic, prompting players to recall playing

Atari games with friends and family members, and it encourages

players to come together with others to enjoy the game.

|

| Francisco Ortega-Grimaldo,

a SWEAT collaborator and founder of the Ludoztli

("making games") movement, created the board games,

Crossing

the Bridge and Observance.

Both deal with U.S./ Mexico border issues. Crossing the

Bridge is a game of chance and is similar to Monopoly

and The Game of Life. The game is designed to illustrate

"the symbiotic relationship of the El Paso-Juarez border

by resembling the cliché of the illegal exchange of

goods between both cities."(47)

Players attempt to smuggle illegal cargo (i.e., food, drugs,

illegal aliens) across the border. Before entering the United

States, however, all cars are searched by the Border Patrol,

and, if caught, the player/driver can loose the cargo, passport,

or car. If a player successfully evades the Border Patrol,

the player is awarded money, which can be used to buy appliances

or cars to be smuggled into Mexico. To win, a player must

get all of the appliances needed to furnish a first-class

home. |

|

|

| Crossing the Bridge

| Francisco Ortega-Grimaldo | 2001 |

|

|

| Observance | Francisco

Ortega-Grimaldo | 2001 |

|

|

Ortega-Grimaldo's

Observance is also chance-based, but the game is

modeled after the war game, Battleship.(48)

Unlike Battleship, however, the goal is not to destroy an

opponent's ships. One player acts as the Border Patrol and

tries to spot and prevent immigrants from entering the United

States from Mexico; the other player acts as a group of

immigrants seeking asylum in a church or seeking a green

card, which has been hidden somewhere on the board. Players

assume the roles of hunter and hunted.

|

| Gabriel

Orozco has created modifications of Ping

Pong, Billiards, and Chess. For Oval Billiard

Table (1996), Orozco has modified Billiards

to be played by "the laws of the universe." He has

reshaped the traditionally rectangular billiard table into

an oval and has suspended one of the three billiard balls

on the end of a pendulum. In doing so he has made the game

highly unpredictable; the swinging ball might hit one of the

balls in its path or an unsuspecting player. In this modification,

players have to create new rules to play. For his 1996 Horses

Running Endlessly, Orozco redesigned the landscape of

Chess and removed all pieces but knights. He has

increased the number of knights to four sets of sixteen and

has increased the number of squares on the chessboard from

32 to 256. In the new landscape, the knights wander aimlessly.

The modification fragments the world of the game. Orozco states,

"You have this fragmentation and then you act. You have

to move things, and then you commit yourself with the movement.

And then, reality is coming back to you. Reality means the

other player. And it's coming back to you with a move that

you probably expect. But it could be a surprise."(49)

In a PBS interview, Orozco talked about games as "expressions

of how we believe the universe works in different cultures

. . . . Every game has a connection to how we conceive nature

and landscape. How we order and structure reality." (50) |

|

|

| Horses Running Endlessly

| Gabriel Orozco | 1996 |

|

|

| Painstation | Volker Morawe

and Tilman Reiff | 2000 |

Volker Morawe and Tilman Reiff

of Fur Art Entertainment Interfaces sought to bridge the on-screen

world of games and the real world of their work in PainStation

(2001). The game is a duel recast as a game of Pong and

is played on an arcade console. Players stand across from each

other, one hand on a controller and the other on a "pain

execution unit" (PEU). Points are not won or lost during

play; however, a player who fails to return a ball successfully

is penalized by a burn, shock, or lash on the hand from the PEU.

The player who first lifts a hand from the PEU loses the duel.

Although players are playing Pong, the game is not Pong

but a test of endurance, testing ability to withstand pain. The

most interesting thing about the piece is what it reveals about

human nature. Players become absorbed in the game, playing to

avoid as well as to inflict pain, laughing at their own pain and

enjoying the pain of the opponent.

|

| Proposition Player | Matthew

Ritchie | 2003 |

Matthew

Ritchie illustrates the nature of the universe in

a game entitled, Proposition

Player. The game is played in two different ways. The

first is generative and is only played by the artist. The artist

plays Poker with a modified deck of cards, and the hands

that are dealt guide the composition of paintings, which are then

created by the artist. Each card has been modified to include

a name and symbol representing a force or dimension at work in

the cosmos (e.g., strong force, weak force, light, gravity, time,

etc.). Some of the paintings that resulted from the game are M

Theory (2000), based on four aces and a joker; Giant

Time (2003), based on four aces; The Eighth Sea

(2002), based on a straight; and After Lives (2002),

based on two pair. There are fourteen in the series. In the generative

version, the artist plays a card game, and the card game prompts

the painting. The second version of the game is an installation,

and the game is not played by the artist but by patrons. The game

is modeled after the casino game, Craps. Patrons roll oversized

dice, and each roll is converted into information that is used

to create a digital painting that is then projected on the wall.

As players continue to roll the dice, they are taken through five

levels of play and a narrative relating the evolution of the universe.

The installation explores the idea of risk and poses the question,

"Is it possible to always win?" The slogan of the game

is "You may already be a winner!"(51)

Ritchie converts the traditional approach of confronting ideas

about the universe with awe to confronting the ideas with an act

of play. He says, "The technology of the playing card is

such a beautiful thing. It's been around for a long, long time.

No one mistakes it for some kind of art-related activity—it's

a playing card. You know you can throw it away."(52)

III. Exhibits

The body of work discussed below

includes examples of the three modes of interactivity that I have

described: static, reactive and interactive. All explore aspects

of war and conflict. In each the coded or rule-based interactivity

is meant to enhance the meaning of the work, not simply to make

it "more sexy." The narrative of each piece unfolds

in the actions of the participants. Players glimpse aspects of

war and conflict by means of a card game, board games, physical

acts, and reflection.

warDecks

Game modification / 52 decks of plastic coated 2 1⁄2"

x 3 1⁄2" playing cards / 2006

| WarDecks is a game modification

in the tradition of Fluxus. To create the piece, I re-sorted

fifty-two decks of playing cards so that each deck contained

only one type of card (e.g., a deck with fifty-two queens

of hearts). I handed out decks to fellow artists, academics

and friends and asked them play War, a card game

for two or more players. The rules are simple and widely known:

the cards in the deck are shuffled and dealt to the players;

each player has the same number of cards; to play a hand,

players simultaneously reveal a card, and the highest card

captures the hand. The object of the game is to capture all

cards in the deck. I did not change the rules of the game,

but I did modify the code. |

|

|

| warDecks| Andrew

Y Ames | 2006 |

|

No one, of course, can ever win

a hand because every card in the deck is the same. But the modification

makes a point: no one can win the game of war. Those who played

the game reported that the modification took all of the fun out

of the game. The experience also makes a point: the game of war

is not fun. At best, the game and its real-world counterpart are

tedious and pointless. The work succeeds in some ways, but fails

in others. Players enjoy discovering that all of the cards in

the deck are identical, and they are amused by the realization

that no one can win a hand or the game. But interest quickly fades

into frustration, irritation, and abandonment. The game is interactive,

but does not sustain interest, and players do not necessarily

associate the game of War with the realities of war.

Well, Let's Just Ba-Bomb the Mushroom Kingdom, Too.

Ink on paper / eighteen 9" x 13" water-based woodblock

prints / 2007

|

| Well, Let's Just Ba-Bomb the

Mushroom Kingdom, Too | Andrew Y Ames | 2007 |

|

|

Well,

Let's Just Ba-Bomb the Mushroom Kingdom, Too, combines

traditional Japanese woodblock printing techniques and contemporary

video-game imagery in a visual comment on the unfortunate

nature of sanctioned and terrorist bombing. I produced eighteen

prints designed for display in a rectangular pattern on

a wall. Each print contains a stylized, cartoon-like image

of a bomb that appears in the Super Mario Brothers

video game. Added to each print is the name of one real-world

city that suffered a bombing (e.g., Oklahoma and Hiroshima).

The title of the piece, like the image of the bomb, alludes

to the video game. In the game, the Mario Brothers attempt

to rescue a princess from the cute and peaceful Mushroom

Kingdom, which they would never consider bombing because

a princess lives there. The title of my piece is sarcastic,

for it would not be prudent to resort to bombing. The piece

is a response to the realization that all bombs—whether

dropped from a plane or hidden in car—shatter bodies

and destroy property and that the horrors of the tactic

cannot be masked and should not be glorified by marketing

slogans such as "shock and awe."(53)

The current practice of marketing war (and, hence, marketing

bombing) offends. It shocks the sensibilities and lends

itself to a response in the Surrealist and Dadaist tradition:

"épatez les bourgeoisie."

|

There is no attempt in the piece

to identify specific nations or conflicts, to organize them geographically

or chronologically, or to distinguish military or terrorist bombings.

These differences are important in some respects, but I want the

viewer to see that all bombings are alike—they destroy;

and there is always collateral damage. A bomb is a bomb is a bomb.

This is emphasized by the repetition and sameness of each print.

The cities differ, but the bomb is the same. Like Super Mario

Brothers, bombing is a game, albeit a deadly game, and one that

should not be played. Ironically, in the Mario Brothers

game only the bad guys drop ba-bombs. The protagonists, Mario

and Luigi, avoid them. The allusion to the game will be missed

by many, and this is a weakness of the piece, but I have kept

the video-game reference because there is something to learn from

the peaceful victory that can be achieved in the video game, and

those familiar with game will appreciate the connection. Players

can win the game without ever dropping a bomb or firing a shot.

Argument

Table game / One wood, plastic and steel 40" x 40" x

45" table, three wood and plastic 29" stools, 54 wood,

steel and plastic game pieces / 2007-2008

|

| Argument installation view |

Andrew Y Ames | 2007-08 |

|

|

Argument is a table game that

allows three players either to collaborate or to compete—the

players decide. The players sit at a round table that has

144 circles inlaid on the top. They take turns moving their

own game pieces from circle to circle. The pieces stack,

and a player who creates a stack of three pieces, removes

and collects the pieces. In competitive play, the person

who removes all of his or her pieces and collects

the most pieces by the end of the game, wins. In collaborative

play, everyone can win, but only if all pieces are removed

from the table.

Setup and play are easy; winning is not. Each player receives

six of each type of piece and lays the pieces out between

three rows. The symbol on top of each piece shows its movement.

Each of the three pieces moves like a familiar Chess

piece: a knight, a rook, and a bishop. In addition, each

type will only stack on a specific type of piece, and the

relationships are similar to Rock, Paper, Scissors:

rock over scissors; scissors over paper; paper over rock.

Players do not have to remember the relationships because

a hole in the bottom of each piece matches the top of the

specific type of piece on which it stacks.

|

The physical structure

of the game was intended to foster collaborative play. Players

sit at a round table as equals. The table is small enough

to encourage intimate conversation, but too large to reach

across easily, so players must help one another move pieces

that are out of reach. Even if players choose competitive

play, they must collaborate with one another in moving pieces.

Watching people play the game has shown that players often

choose to compete, and the competition reveals something

about human behavior: when players collaborate, they are

talking to one another; when they compete, they talk much

less or not at all. These behaviors seem to increase as

players become more familiar with the game. When playing

collaboratively, the game is more like a puzzle than a board

game, for players must have open communication to plan a

strategy to clear the board. People enjoy playing the game,

and because it requires three players, it does bring people

together. Players decide how to play, and the decision changes

how they interact with the game and with one another. |

|

|

| Argument table top detail | Andrew

Y Ames | 2007-08 |

|

The Box Game

Box # 8, 12, 11, 11, 8, 7, 2, 6, 2, 2, 1 / Zebra-wood, padauk,

and walnut kerfs 11" x 8" x 7" / 2007

Box # 6, 11, 5, 7, 12, 2, 4, 3, 6 / Bloodwood, maple and walnut

kerfs 5" x 7" x 12" / 2007

|

| Box#8 & Box#7 | Andrew Y

Ames | 2007 |

|

|

The Box Game is very much in

the tradition of Surrealist automatism, for it is a game

that is used to select materials, establish dimensions,

and determine the number of kerfs in the construction of

wooden boxes. First, two dice are rolled to determine a

type of wood to use. Twelve types of wood were numbered

I through XII. The number on the dice corresponds to a type

of wood. If the roll includes the number one, then wood

type I is used, as well as the type of wood that corresponds

to the sum of the dice. For example, if a one and a four

are rolled, wood types I and V are used. If doubles are

rolled the player may use two types of wood, the first being

the sum of the first roll and the sum of the second roll.

Second, players roll two dice to determine the type of wood

to insert into the kerfs. Third, players roll two dice three

times to determine the height, width and depth of the box.

Fourth, players roll one dice four times to determine how

many kerfs are used on each edge of the box. Fifth, players

must make a lid from the remaining woods to fit the width

and depth of the box. The box is then titled using the numbers

rolled. Chance acts as a guide, and the rules, I discovered,

are surprisingly freeing, allowing the maker to focus on

the process not the design.

|

With this method I created two boxes,

box # 8, 12, 11, 11, 8, 7, 2, 6, 2, 2, 1 and box

# 6, 11, 5, 7, 12, 2, 4, 3, 6. I put a unique set of holes

in the lids of each box, encoding how and who could open them.

With box # 8, 12, 11, 11, 8, 7, 2, 6, 2, 2, 1 five holes

were laid out so that the fingers of a typical adult's right

hand could slip into the lid allowing it to be lifted off. With

box # 6, 11, 5, 7, 12, 2, 4, 3, 6, four holes were added,

two on either side of the lid, allowing a child's index

fingers and thumbs to slip inside the box to lift off the lid.

The holes are intended to capture a viewer's curiosity,

and when the boxes are displayed, viewers were observed reaching

out and removing the lids of the boxes. Viewers do experience

a measure of inner conflict: the boxes raise curiosity, but viewers

cannot see what is in a box before slipping fingers and thumbs

inside. Their fingers act like a key; if their fingers do not

fit, the contents of the box remain a mystery.

Mano a Mano

Installation / Regulation-sized 38" x 26" x 40"

arm-wrestling table, 2" x 3" x 66" speaker boxes,

walnut, steel, leather and custom electronics, 10' x 10'

canvas mat / 2007-2008

Mano a Mano is

a regulation-size arm-wrestling table built on massive

legs. However, it is not a regular arm-wresting table.

The rusty steel top, worn leather elbow rests, and sweat-stained

pin pads, and walnut enclosure conceal electronics that

sense and process the wrestling match. Players discover

that the table reacts to the back-and-forth movement of

their interlocked grip. The table detects hand and arm

location as players exert force and press for victory,

and the table responds by playing pre-recorded sounds.

Arm wrestling stirs images

of muscles and gambling: power and greed on a man-to-man

scale; one-on-one competition across and around a back-room

table. The design of the table evokes but also extends

the image. The massive, square design recalls the imposing

shape of a fortress with corner towers. Players become

soldiers who look one another in the eye and, while they

compete, hear the voice of an unseen person: a drill sergeant

barking orders. The voice, however, is female. She calls

out passersby, outlines rules, starts the contest, chides

those who cheat, and berates underachievers. The table

borrows an image from the battlefield and a voice from

boot camp.

|

|

|

| Mano a Mano installation view

| Andrew Y Ames | 2007 |

|

|

| wrestling match |

|

|

Mano a Mano is a metaphor.

Soldiers engage in hand-to-hand combat and hear a master

sergeant's instructions. The sergeant berates, and the language

is sexist and abusive; it is a language that creates warriors.

They are not praised or encouraged; they are insulted, and

this goads them. The voice deforms their humanity and devalues

what they defend. They are little girls, not valiant men,

yet wars are said to be fought for those back home. War

dehumanizes, and the voice of war dehumanizes soldiers.

They are incited to fight by verbal abuse. Ironically, the

abuse does not come from the opponent but from the sergeant,

and those who play the game seem to derive a measure of

satisfaction from it. The work emphasizes the liminal and

crosses boundaries: game and war; wood and steel; worn table

and new technology; male stereotype and female voice; victory

and pain. |

Rock Paper Scissors Bomb

Sculpture / 15"x 42"x

38" walnut pedestal, American rock, Japanese paper, German

scissors, and an inert hand grenade / 2008

Rock Paper Scissors

Bomb is an iconic representation and modification

of the hand game Rock Paper Scissors, (also known

as rochambeau or jan-ken-pon) in the

tradition of the Dadaist readymades. I have changed the

code of the game from hand signals to the actual objects,

and changed the rules by including a bomb, specifically

an inert hand grenade. Although it is nothing new to add

a fourth item to the game–for example, one set of

rules includes dynamite which can beat rock and paper

but is defeated by scissors because they are able cut

the dynamite's fuse–the bomb trumps everything.

I only include one of each item, shifting the game of

chance to a game of speed. The game becomes a race for

players to reach the strongest item first. Although this

piece is designed to be static, it has an implied interactivity

allowing viewers to contemplate how they might play.

No one can play this game,

but one can imagine racing for the bomb. In this modification

the bomb unseats the balance of power and puts the viewer

in a cold war mentality: "if I reach the bomb first

I know I will win." This implicates the viewer and

the desire for power, and raises the question of motive:

Is it a fear of losing or a need to win that evokes a

race for the bomb?

|

|

|

| Rock Paper Scissors Bomb | Andrew

Y Ames | 2008 |

|

Last Resort

Game modification / 10" x 10" x 1" walnut and sand

chessboard, walnut and brass pieces / 2008

|

| Last Resort | Andrew Y Ames

| 2008 |

|

|

Last Resort is a modified game

of Chess in which two opposing sides wage war to protect

civilians and territory. The Bleached side consists of eight

pawns, two rooks, two knights, two bishops, and a nuke;

the Oiled side has eight pawns. Neither side has a king

or a queen. The game itself has six civilians. The chessboard

has alternating walnut islands and black sandpits. The game

of Chess traditionally represents war between kingdoms,

and the kingdoms have equal power, observe the same rules

of engagement, and pursue the same end: to overpower the

opposing king. The distribution of power in real war, however,

has always been asymmetrical. War today is rarely an attempt

to unseat a king, and contemporary wars are not fought by

military forces of equal strength; the differences between

sides may be enormous. Traditional rules of engagement are

not necessarily observed. The conflict may not even involve

one nation against another nation, and the distinction between

military and civilian participants is blurred. Last

Resort modernizes the game of Chess by mimicking

these aspects of real war. Each side has its own code. The

Bleached side, which represents strictly regimented soldiers,

wages war to protect the citizens of a foreign territory;

the objective is to liberate a people believed to be oppressed.

The Oiled set of pieces represents autonomous soldiers who

fight to protect their freedoms and to recruit citizens

to support their causes. Players on both sides seek to protect

life and freedom, but they do so for very different reasons.

One fights to free a foreign people in another land; the

other fights to be a free people in their own land. |

The asymmetry of war is

encoded in the pieces and their movements. The Oiled player

has eight pawns that move, at the discretion of the player,

like a rook, knight, or bishop, though no more than three

squares at a time. The Bleached player has eight pawns,

two rooks, two knights, and two bishops that move like

conventional chess pieces, plus one nuke that moves one

square in any direction. The game also has six civilian

pieces that either player may move diagonally one square

at a time. Players take turns moving one of their own

pieces or one of the civilian pieces. Players can move

pieces to empty squares or squares occupied by opponent

or civilian pieces. Moving to an occupied square removes

the occupant from the board. Oiled pawns and the nuke

may be detonated or moved. To detonate an Oiled pawn,

it and all adjacent pieces are removed from the board.

Detonating the nuke removes the nuke and all pieces within

three squares of the nuke. During a turn, a player can

either move or detonate a piece but cannot do both. The

first player to move four civilians to the row closest

to their side of the board wins. If three or more civilians

are removed from the board, the player who removed the

fewest civilians wins.

|

|

|

| Pawn & Civilian detail |

Andrew Y Ames | 2008 |

|

I've created a situation where the citizens are the most valuable

piece of the game, the key to winning is not strictly through

annihilating your opponent, but through the people effected most

by the conflict, those caught in the middle. In the game players

can choose to play justly and protect the citizens. Or manipulate

civilian loses to gain support through deception. Further, its

an attempt to humanize the act of a suicide/ martyr bombing an

act done out of desperation in hopes to sway the odds of an uneven

playing field.

|

| Notes

(1) Erkki Huhtamo, "Silicon Remembers

Ideology, or David Rokeby's Meta-Interactive Art (from

the Catalog for 'The Giver of Names' Exhibit at the

McDonald-Stewart Art Centre)" (1998)

http://

homepage.mac.com/davidrokeby/erkki.html

(accessed April 26, 2008)

(2) Randi Hopkins, "Collision Collective

at Art Interactive and Urban Icons At the New Art Center,"

The Boston Phoenix, March 25, 2005

http://www.thebostonphoenix.com/boston/events/galleries/documents/04551270.asp

(accessed April 26, 2008)

(3) Art Interactive, "Curatorial

Mission Statement" (2005)

http://www.artinteractive.org/curatorial.php

(accessed April 26, 2008)

(4) Noah Wardrip-Fruin, "Expressive

Processing: On Process-Intensive Literature and Digital

Media" (Ph.D. diss., Brown University, 2006), 2.

(5) James Paul Gee, What Video Games

Have to Teach Us about Learning and Literacy (New

York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003)

(6) Marc Prensky, Digital Game-Based

Learning (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001);

see also David Gibson, Clark Aldrich, and Marc Prensky,

Games and Simulations in Online Learning: Research

and Development Frameworks (Hershey, PA; Information

Science, 2007)

(7) The concept of "strongly interactive"

art is drawn from Dominic Lopes, "The Ontology

of Interactive Art," Journal of Aesthetic Education

35 (2001): 65-81

(8) See comments on the "observer"

in Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On

Vision and the Modernity in the Nineteenth Century

(Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992)

(9) "Monopoly History," Hasbro.com

http://www.hasbro.com/games/kid-games/monopoly/default.

cfm?page=History/history

(accessed April 26, 2008)

(10) See also the game, Anti-Monopoly

by Ralph Anspach (http://www.antimonopoly.com)

(11) Martin Gardner, "Mathematical

Games: The Fantastic Combinations of John Conway's New

Solitaire Game 'Life,'" Scientific American 223

(1970): 120–23

http://www.ibiblio.org/lifepatterns/october1970.html

(accessed April 26, 2008)

(12)"Golly," Sourceforge.net

http://golly.sourceforge.net

(accessed April 26, 2008)

(13) Eric Zimmerman, "Narrative,

Interactivity, Play and Games: Four Naughty Concepts

in Need of Discipline," in First Person: New

Media as Story, Performance and Game, ed. Pat Harrigan

and Noah Wardrip-Fruin (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004),

154–64

(14) Lopes, "The Ontology of Interactive

Art," 67

(15) Ibid., 68

(16) Noah Wardrip-Fruin, "Playable

Media and Textual Instruments" (2005)

http://www.dichtung-

digital.com/2005/1/Wardrip-Fruin

(accessed April 26, 2008)

(17) Graham Coulter-Smith and Elizabeth

Coulter-Smith, "Art Games: Interactivity and the

Embodied Gaze," Technoetic Arts: A Journal

of Speculative Research 4 (2006): 169-82

(18) Ibid., 169

(19) Ibid., 179

(20) Ian Bogost, Persuasive Games:

The Expressive Power of Video Games (Cambridge,

MA: The MIT Press, 2007). 28

(21) Thyrza Nicholas Goodeve, "Reflections

on an Omnivorous Visualization System: An Interview

with Matthew Ritchie," in Matthew Ritchie:

Proposition Player, ed. Lynn Herbert (Houston,

TX: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2004), 43

(23) Ernest Adams, "Dogma 2001:

A Challenge to Game Designers," Gamasutra.com (February

2, 2001), http://www.designersnotebook.com/Columns/037_Dogma_2001/037_dogma_2001.htm

(accessed April 27, 2008)

(24) Cory Arcangel, "Cory Arcangel—Digital

Media Artist," Art & Technology Lectures (Columbia

University School of the Arts Digital Media Center,

2004)

http://www.columbia.edu/itc/soa/dmc/cory_arcangel

(accessed April 27, 2008)

(25) Christiane Paul, Digital Art

(New York: Thames & Hudson, 2003), 201–3

(26) Nic Kelman, "Yes, But is it

a Game?" in Gamers: Writers Artists and Programmers

on the Pleasures of Pixels, ed. Shanna Compton,

(Brooklyn: Soft Skull Press, 2004)

(27) Claudia Mesch, "Cold War Games

and Postwar Art," Reconstruction 6 (Winter 2006),

par. 3

http://

reconstruction.eserver.org/061/mesch.shtml

(accessed April 27, 2008)

(28) The Nocuchi Museum exhibition was

open October 21, 2005 through April 16, 2006 (Exhibitions

& Collections

http://www.noguchi.org/imagery_chess_past.html

(accessed April 27, 2008])

(29) Larry List, "The Imagery of Chess Revisited,"

in The Imagery of Chess Revisited

ed. Larry List

(New York: George Braziller, Publishers, 2005), 16

(30) Ibid

(31) Ibid., 97–99

(32) Ibid., 30

(33) Jerrold Seigel, "Loving and

Working," in The Private Worlds of Marcel Duchamp:

Desire, Liberation, and the Self in Modern Culture

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 209

(34) Ibid., 211–12

(35) Ibid., 211

(36) Quoted in A Book of Surrealist

Games, comp. Alastiar Brotchie and ed. Mel Gooding

(Boston, MA: Shambhala Redstone, 1995), 137

(37) Ibid., 25

(38) Ibid., 154

(39) Ibid. 84-83

(40) Mesch, "Cold War Games and

Postwar Art," par. 26

(41) Ibid., par. 19

(42) "Web Video Game Aim: 'Kill'

Bush Characters," CNN.com, September 18, 2006

http://edition.cnn.com/2006/WORLD/meast/09/18/bush.game

(accessed April 27, 2008)

(43) Waffaa Bilal, "Waffaa Bilal's

Response to President Jackson Regarding the Closure

of His Exhibit," Virtual Jihadi

http://wafaabilal.com/statement.html

(accessed April 27, 2008)

(44) Natalie Bookchin, "The Intruder,"

Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 26 (2005): 43-47

http://

www.netarts.org/mcmogatk/2003/works/harger/intruder.html

(accessed April 28)

(45) Ibid

(46) http://maryflanagan.com/joystick/default.htm

(accessed April 27, 2008)

(47) Francisco Ortega-Grimaldo, "Observance,"