Keywords

Feedback, acoustics, improvisation,

industrial feedback, acoustic feedback

Abstract

This paper deals with my fascination

for acoustic feedback. From an artistic point of view, I will

describe several types of feedback, and give descriptions, drawings

and images of works we made based upon these different types,

as well as links to videos and mp3s. Besides that, I want to express

my doubts, theories, and questions, as well as our motives and

enthusiasm for using this medium.

An introduction and

three anecdotes:

First let me introduce myself: Mario

van Horrik from the Netherlands. Together with my wife, Petra

Dubach, I work with the media movement and sound, mostly. Through

the years, we have presented sound/movement installations, performances

and concerts in museums, galleries, factory halls, mine buildings,

open air, concert halls, an abandoned synagogue, and other odd

places around the world.

Petra comes from a dance background,

I from the music. We are both in our early fifties and we feel

we've come a long way to where we are now. To be honest,

we are not sure where exactly this is and our work doesn't fit

the usual artistic disciplines or predicates any more. That happens

to people who get involved with feedback, as you will find out.

1.

For me, everything started when I was a little boy, from a traditional

family in the southern part of the Netherlands. I was the youngest

of 11 children, and my 5 brothers and I slept in the attic of

the house. Since I was the youngest, I had to go to bed first,

and I always tried to stay awake until my older brothers would

come to bed. In so trying, I used to open the small attic window,

which I could reach from the end of the bed. If I stretched myself

a bit, I could just look outside, with the cold iron of the window

frame against my cheek. About a mile away from our house was the

railroad track, and the big mystery for me was that I sometimes

could hear a train, but couldn't see it; and sometimes I

could see the train, but not hear it.

2.

When I was a bit older, I watched one of my brothers, a carpenter,

saw a piece of wood. I asked him if I could help, so he let me

saw a piece of wood. After a few minutes, I was exhausted, and

complained about it, when my brother told me: "You have to

let the saw do the work."

3.

In the late 70's, when I was (still) a good looking, young guitar

player, who had given up the dream that some day I would be as

famous and as great a genius as Jimi Hendrix, I saw in a British

magazine a picture of the British composer and musician Steve

Beresford. In his hand, he held a guitar with clothespins clipped

on the strings. I was intrigued, and tried the pins on my guitar.

It sounded shitty, but soon I found myself playing on 3-stringed

guitars, prepared with sticks, beads, etc. Years later I met Steve,

and told him about the picture, and how it had inspired me. He

laughed and told me that the pins had been put on the strings

to make the picture look more interesting.

Types of feedback.

People may use feedback occasionally,

as a small part in a bigger whole, like guitar feedback in pop

music. That's not what this is about. We are using feedback as

a conceptual basis for our work. We are searching for the ‘bone'

of sound. We are not scientists, so our characterization of types

of feedback maybe not be accurate or complete; however it is based

on our practical experience. The types of feedback that I am acquainted

with are:

• Direct acoustic feedback:

direct contact between speaker and sound source (for instance

when you place your electric guitar against the speaker box).

• Indirect acoustic feedback:

the process that takes place through the air (microphone in front

of speaker)

• Industrial feedback: the

system of measuring and controlling, mostly performed by sensors,

and electric circuits.

• Improvisation: play acting

(controlling) and reacting (measuring) between 2 or more people

simultaneously.

• Combinations of the above.

Techniques.

The simplest technique for creating

acoustic feedback is to put a mike in front of a speaker, and

turn up the volume of the amp to the point that the feedback will

build itself up. If you leave it like this, eventually your ears

and gear will be ruined. The frequency ‘picked' by the equipment

is determined by the quality and acoustic properties of the amp,

speaker, microphone, and the space. I don't know if a formula

exists that will make it possible to make calculations, but to

me it seems to be impossible.

Anyhow, the first conceptual acoustic

feedback-piece I know of is Pendulum Music (1968) by Steve Reich,

who used 3 microphones/amp/speaker-sets. The mikes hung from the

ceiling on different lengths of cable, and were swung. The tempo

varied because of the differences in cable-length, and passing

the speaker, a short feedback sound came from the speaker. The

piece ended when the sound was continuous, because the swinging

had died out. Other artists use feedback as a trigger: they have

a microphone or instrument making feedback, and load the sound

into an electric circuit, that itself may also be a feedback system.

They use filters and effects to shape the feedback sound into

material they can use further with computers, samplers, etc. They

are what I call the ‘in-betweens'; the method allows them

to keep control, and express their sonic ideas in structures under

their supervision; whereas Reich's concept is radical: the saw

does the work, so to speak.

Description of some

pieces, according to types of feedback:

Het Vogelbekkenstuk.

(Direct feedback). Concert piece.

In 1988, we conceived the

piece Het Vogelbekkenstuk. The piece is a statement about

movement and sound.

There are 2 identical instruments;

each consisting of 2 hinged wooden beams, with a string

and spring stretched between the 2 ends of the beams,

(Figure 1). The strings have a piezo-pick-up, and the

amp/speaker stands on the lying beam. With the volume

turned up loud enough, the system will produce direct

acoustic feedback (the acoustic feedback takes place because

there is a direct contact between the instrument and the

amp/speaker).

Each player holds one instrument, and tries to stand

as still as possible. We didn't succeed in remaining still,

but this is something that can't be seen, it is only heard.

We look static, but whalelike, gliding sounds come from

the instruments.

Sometimes, for a short while the sounds are stable and

fixed, but then something changes again, interferes, etc.

Originally, I made the instruments so that the strings

would be plucked, but during the soundcheck of a concert,

on a hollow stage, the instruments started to give us

feedback. It took quite some time to get rid of it.....So

you see, strange coincidences can happen, and in this

case (as is in most) my brother was right: we did let

the saw do the work.

|

|

|

Figure 1 (above):

Het Vogelbekkenstuk. Photo:Wim Janssen. Performed

at Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

Below: Sound sample of Het Vogelbekkenstuk |

|

|

DioN.Y.sus' Scales.

(Industrial feedback).Installation.

A completely different type of feedback,

maybe unfamiliar to most artists, (although it is a part of everyday

life) is industrial feedback. I was first told about it in 1991by

professor Zweitse Houkes from the Technical University of Enschede

in the Netherlands. He explained to me that industrial feedback

is a system of measuring and steering (or controlling) to create

certain results. For instance your central heating system: if

you want your living room to be 20 degrees Celsius (68F), you

set your control to20C. If it is colder, the heater will start

heating until it is 21C (69.8F). Then it stops, and starts again

when it is 18C (64.4F). Temperature is measured, heater switched

on or off: simple.

In industry, feedback is used to

have very precise control over processes: to have pieces of wood

sawn in the exact format and shape needed; to have parts of trains

interlock precisely, and to produce as many clothespins a day

as possible. So, I wondered if I could make a feedback system

that would be useless (art), and especially unpredictable in what

it produced and when. I didn't want it to be precise and exact,

but to find the widest limits possible.

I was lucky, and got an invitation

to do a show in Art in General in New York City, as well as a

residency at Harvestwork's Studio Pass in 1994. Besides that,

several Dutch institutions were so kind to spend a great amount

of money on my new work to be shown at Art in General: DioN.Y.sus'

Scales. The basis of this installation was a performance called

‘the Boxing-ring' that Petra and Iperformed several times.

|

|

|

The basic construction is 4 strings tensed

vertically from floor to ceiling, with piezo pick-ups mounted

on the strings, and a metal ring at hip height. Ropes stretched

horizontally between the rings make the instrument look like

a boxing-ring. On cross-strings a steel and an aluminum stave

were attached to it. I would play the instrument from the

outside with sticks, a bow, my voice and an electric razor,

while Petra performed inside the ring; pulling the ropes,

hitting them, leaning against them, etc. and, in this way,

tuning the sounds and adding sounds. So the Boxing ring was

automated. Four motors, mounted on the floor, pulling and

releasing ropes extended the basic form (see video). We employed

weighing scales (the type with a spring and hook, used to

weigh sacks of potatoes) with a sliding potentiometer (like

the volume controls from a mixing board) attached to it, to

measure the pulling force and translate it into voltage. The

piezo-pickups were used as vibration sensors as well. Henk

Goossens and Erik van de Poel, two enthusiastic Electrical

Engineering students of Eindhoven Technical University designed

and built me the fantastic piece of equipment that allowed

me to input all the pulling and vibration measurements. These

were used to steer the output volumes to the 4 amp/speaker

combinations. Volumes increased or decreased according to

a more or less pulling force or vibration on a string, with

a possibility to shut down the volume-output from 4 seconds

to 4 minutes, using peak-level measurements from other sources.

The piezo-pickups also delivered variable voltage for the

4 motors on the floor, with a protection that changed poles

when the pulling force was reaching a limit; and to change

poles as well through a peak-level measurement on one of the

strings, for example. And it had the same possibilities for

several smaller motors, such as a motor driven bow; a ‘rattler,'

a propeller, etc, to play the instrument. This electronic

device gave me the opportunity to connect whatever with whatever;

and the result was amazing. |

There was a seemingly uncontrolled

and uncontrollable moving, silent, screaming, resting, breathing,

grim, grinding, growling beast; completely unpredictable, because

too many things happened at once. Most fascinating for me was

the discrepancy between the electronics and the material: sometimes

a string was pulled out of reach of the motor that was supposed

to play it; sudden movements made metals swing out of reach of

its player-motor, etc. The whole system pulled its own leg.

And so you see...hearing a train

and not seeing it (or the other way around) is peanuts compared

to the things you may cause yourself once you're an adult.

Flexitar. (Improvisation).

Concert piece.

Another type of feedback we have

come across is similar to the industrial feedback, but is performed

by people. In that sense, every piece of improvisation is a performance

of this type of feedback; that is, if it is performed by at least

2 persons simultaneously. The purpose is, of course, to make music

together; and because you can't tell what your music partner will

do, you have to be very alert. Sometimes you 'work together',

and sometimes you try to get your partner to 'follow' or change

what he or she is doing. So you might call it mental, aural or

physical feedback. I conceived the piece Flexitar in 1988, first

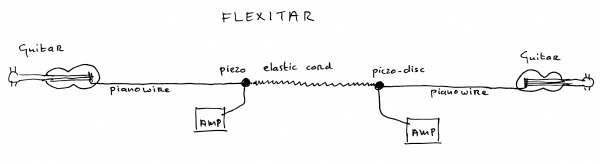

as a solo piece. The setup is like this:

A long string is woven through the

3 strings of a guitar and it ends in a piece of elastic cord that

is attached to a fixed object, like a wall. At the point where

the long string (minimum length 3 meters) is connected to the

cord, a piezo pickup is clipped on the string with a clothespin

(!). When playing the guitar strings, something weird happens:

somehow the transversal vibrations of the guitar strings are being

transformed into longitudinal vibrations in the long string. This

means, that you don't need much tension on the long string to

make it sound.

By using the elasticity of the cord,

I have some freedom to move a little bit (maybe one meter, depending

on the length of the elastic cord), and in that way I can 'tune'

the long string. Sometimes, when playing one guitar string, up

to five layers of sound frequencies occur from the long string,

ranging from very low to very high. When 'tuning', this changes:

the low frequencies have a tendency to change slowly, sometimes

they disappear; sometimes they slowly glide into another higher

or lower, more or less for some time 'fixed' pitch.

The highest frequencies change very

fast, already when I shift my weight from one leg to the other.

|

Figure 2 (above): Flexitar.

Drawing by Mario van Horrik.

Below: Sound Sample of Flexitar. |

|

When we play the piece together, the construction is like this:

guitar-long string-elastic cord- long string- guitar. (Figure

2). Then, the process becomes more complex of course. Partly,

in the space the sounds of the 2 long strings interfere, merge;

and because neither of us can stand completely still while playing,

the sounds change all the time. The aim is to make a sound piece

that is interesting in its development, with climaxes, changes,

etc.

The problem is that one of us may

not understand what the other's intentions are. So, when one of

us likes to continue what we were doing, the other may wish to

introduce some change. When this is a big change, then it's obvious,

and there's not much the other one can do to prevent it. With

small changes, some kind of struggle between us is often the result.

In fact, we place ourselves in a difficult situation, because

the sounds are not really pitched, and they also change rapidly.

And if Ishift my weight to my other leg, it not only changes my

sounds, but also those of Petra; and she may not like that, and

may try to recreate what happened before, etc.

To be quite honest, we are lucky

to have such a stable relationship, because sometimes our domestic

disagreements are the major subject of a performance of Flexitar.

You, the listener don't have a clue, of course, and thank God.....But

the thing is, that if you place yourself in an ‘uncertain'

circumstance, you need another way of communicating (feedback)

and the more often you do this, the more sensitive you think you

are for it.

But that's the nice thing about

feedback, isn't it? Nothing is certain.

Interference. (Direct feedback).

Installation and performance.

This is a sound installation conceived

in 2001, using direct feedback. But the feedback is being

disturbed by itself. From the ceiling 3 copperplates,

dimensions 1x2 meters and 3mm

thick, hang, each on two strings, one with a piezo-pickup

(Figure 3). Against each plate

stands a Fender Sidekick 30 speaker/amp. The volume is

turned up to the point that the acoustic feedback occurs.

The pickup is positioned so that a low-pitched, sonorous

sound comes from the speaker. The sound builds up, until

the plates start ‘shaking'; causing them to move

away from the speaker, fall back, etc. In this way, higher

pitches are added to the drones. Elements like draft,

and movements of people influence the sounds as well.

Petra performed a piece several times, in which she gradually

increased her tempo while walking around the plates. It

ended with her sudden stop, and the plates swinging, hitting

the amps, etc, until they gradually came to rest, and

the feedback could build up again. In fact, it's quite

paradoxical: the feedback is disturbed by movement (wind).

Haven't I noticed

this before sometime?

|

|

|

|

Figure 3: Interference. Photos by Petra Dubach. At Mine

Building, Waterschei Belgium. |

|

The Chaotic Drumming Machine. (Industrial feedback).

Concert piece and installation.

Very recently, when I was working

with the steering machine that was built for DioN.Y.sus' Scales,

I had an amplified string played by a little motor with a rope

at the axel, like a propeller. The machine was set so that the

motor got just enough voltage to make it turn. If it would hit

the string, the vibrations of the string would increase the voltage

fed to the motor. So, I expected the voltage to build up to the

max, like in a normal feedback, and in no time the motor to be

hitting the string full speed. First it did, but when I limited

the maximum voltage and decreased the gain for the motor a bit,

something strange happened: the motor ran at a certain speed,

for some time, accelerated, slowed down, stayed stable for a short

while, slowed down, etc.

|

|

|

Figures 4 and 5: Chaotic Drumming Machine. Drawings by Mario

van Horrik |

It had become a random voltage motor (Scheme: Figures 4 and 5).

I have no explanation for it; maybe one of you scientific wizards

can explain it? Anyhow, later I used this circuit like this: five

strings of different length (between 15 and 25 centimeters), material

(such as phosphor bronze, piano wire, copper) and thickness, are

clamped in between two metal bars. The bars have one pickup. The

propeller motor (this time with a double elastic cord as a propeller)

hits the ends of the strings. The motor is mounted on a table

microphone stand. It is an amazing drumming machine: it has some

kind of chaotic basic beat that alters the tempo all the time.

Besides that, the strings get hit at fast tempo, but most of the

time ‘dance' away from the motor's reach; plus the elastic

cord makes strange, irregular movements while playing the strings.

It sounds very, very irregular and virtuoso, yet with some ‘steadiness'

in it. I'm planning to use it as an installation, but also in

concerts, changing the position of the motor. Let the (electric)

saw do the work......

|

|

Figure 6 and 7: Donar's Chariot. Photo by Mario van

Horrik. At Islip Art Museum, Islip, Long Island. |

|

|

Donar's Chariot

(Combined direct acoustic feedback and industrial feedback).

Installation.

This sound installation was conceived in 1991. In a space,

2 steel cables are horizontally stretched between 2 walls.

A stripped children's carriage is resting on the steel cables.

Attached to its frame is a long string, ending in a long elastic

cord, that is attached to the wall. A piezo pickup is put

on the long string, near the place where it meets the elastic

cord. An amp/speaker combination hangs under the carriage,

as a counterweight (Figure 6 and 7). The speaker voltage is

fed into a voltage-amplifier that feeds a permanent magnet

motor that is mounted on the carriage. The motor pulls a rope

stretched between the two walls. What happens is this: the

volume of the amp is set, so that the installation produces

direct acoustic feedback. And because the speaker is 'fed',

the motor will pull the rope, and the

carriage will drive over the steel cables. Because it moves,

the tension on the string/elastic cord construction changes,

and the feedback sounds change pitch, so it builds up again,

and so on. Sometimes the produced sound is so loud, that the

system pulls itself through these 'dead points.' When the

carriage reaches a point near to one of the walls, a switch

changes the poles of the motor, so it will drive backwards,

etc, etc. |

Slow Motion (Indirect feedback). Performance

and installation.

Conceived in 2006. For us

this is a wondrous piece, because the indirect feedback

sounds and the process of controlling them are combined

in the same system, in this case: instrument. The basic

setup is an acoustic guitar with a guitar pickup on a

stand. At some distance, an amp/speaker combination is

placed on the floor. The guitar may have 3-5 strings.

A stick of wood or metal is woven through the strings.

The result is a combination of the qualities of the space,

the position in the space of the guitar and the amp/speaker

combination, the distance and position of amp and guitar,

the tuning of the guitar strings, and the position of

the stick.

|

|

|

So you can imagine that there is no such thing as an ‘ideal'

setup, but there will always be some kind of result, and decisions

will be made, eventually....... When the volume is turned up loud

enough, one of the guitar strings will start to resonate; the

stick resonates with it, and will cause the other strings to vibrate

as well. In the same time, this will prevent the system to run

wild, because it would take too much ‘energy.' This means

that sometimes the system will build itself up, and die out, builds

up, etc. It produces cycles that may last several seconds, and

they are quite complex and unstable. Sometimes, the stick will

‘walk' a bit, so the cycles become part of a longer cycle.

Also, it happens that the system finds a balance, and the sound

seems to be stable, and doesn't change. But then (and this happens

in all circumstances), as soon as I change my physical position

in the space, these sounds change as well. It may be, that one

layer of the sound will be more emphasized then before; it may

be that cycles become longer or shorter; it may be that the sound

becomes louder or softer, or that silences during cycles become

longer or shorter; it may be that unstable cycles change into

stable sounds; it may be that the sound color changes. Mostly

we work with a setup of 2 string instruments, each with its own

amp/speaker. This complicates the result enormously, because the

sounds of both systems interfere with one another, and cause even

more unpredictable changes and processes. Also, in our experience,

this seems to increase the influence of a person slowly moving

in the space upon the resulting sound. The body in the space 'disturbs'

the complex of standing waves; small movements can cause remarkable

differences. In addition, we have experienced that the system

needs some time to 'react' to these movements and so Petra usually

moves around with very slow movements; that also explains the

title of the piece.

When we present the work as an installation,

the public will cause some of the changes in the sound when moving

through the space.

Gesamtkunstwerk.

Many artists, who use acoustic feedback

as a concept for their work, describe the influence of movement

and space on its functioning. Draft, wind, doors and windows opening

or closing, people passing by, the positioning of people, objects

in the space, changes in their position, materials of the space

and the architectural forms and dimensions of the space, the positioning

of the speakers, etc,etc. You might call these pieces "Gesamtkunstwerke."

The complexity is enormous, because of all the influences mentioned

above. It may sound foolish and naive, but sometimes I think that

a feedback piece is the expression of theories like quantum physics,

or (how appropriate) the string theory; of which I understand

nothing of course, but still.......

(don't laugh; I'm only an artist

who was already fooled by Steve Beresford and his clothespins).

What I'm really trying to say here, is that the phenomenon is

so fascinating and complex, that the ‘normal' musical ‘rules‘,

or any other rule is not applicable. The best way to deal with

acoustic feedback is to expect nothing; gradually you may become

like me (or some Zen-figure) who spends more time listening to

the wonders of a system that changes all by itself and all the

time in a very subtle way, than may be good for him. You turn

into a loner, endlessly turning his head (like a slow-motion head

banger) to hear the most minimal differences.

Now you might think that us, feedbackfreaks

are weirdos who hear things nobody else can hear; maybe we are

weirdos, but everybody can hear the differences that occur. Maybe

it needs some training and getting used to listening to it, but

eventually you'll see (no:hear).

Yes, feedback is THE drug. And so,

it's not only a Gesamtkunstwerk, but it also becomes a lifestyle.

Because the feedback feeds back

on the way I think and act. Take for instance my attitude: a ‘normal'

musician or composer likes to be in control of what he or she

plays or composes. I used to be like that. But gradually it seems

to become more appropriate and interesting to find out ‘what

the materials and systems themselves have to say.' This means

that my goals have instead become questions; control has become

curiosity.

To take it even a bit further: it

seems like I'm no longer ‘mastering' the process of experimentation;

there is a feedback from the results back to me; they seem to

give me new directions that I can follow up.

Final anecdote.

A few months ago, I was preparing

for a performance of the Slow Motion piece. I had spent several

hours in our studio working with a setup of a guitar and a laud

(Portuguese lute-alike), tuning the instruments, positioning the

amp/speakers, listening, walking around slowly, smoking one cigarette

after another, with the instruments feedbacking all the time.

Then I decided to go to the kitchen to make tea, and when I reached

the door to step out of the studio, it became quiet....... I was

amazed, and slowly turned around. The sound built up again.....

There are a few possible explanations

for what happened. Although very, very unlikely, it could be possible

that the instruments were silently laughing at me: "This

old fool thinks that after 30 years he knows something!! Let's

teach him a lesson." Of course, I never believed in this

ridiculous theory. The following explanation of course is far

more appropriate: when you work together, you also develop a relationship.

The guitar and laud were of course sad that I left, and they were

afraid that I would never come back. It was a misunderstanding,

we talked it over, and we agreed that it would never happen again.

|