|

Introduction

Ever since its inception, people have

used the technology of the Internet to represent

themselves to the world. Sometimes this representation

is a construction based on who they are outside the

network, such as with a personal webpage or blog. Other

times people use the built-in anonymity of the Internet

to explore and engage alternative identities. This

identity tourism (Nakamura, 2002) takes place within

game spaces (e.g. MUDs, MMORPGs), chat rooms, or forums,

as well as within those spaces already mentioned such as

webpages and blogs. In each case, the underlying

technology that facilitates this network society of

digital representations is software. How this software

is designed by its creators determines the ways that

users can (and cannot) craft their online

representation.

The most popular network space for

personal representation is Facebook, the world's largest

online social network. The site has more than 500

million active users and has become the most visited

website in the United States, beating out Google for the

first time in 2010 (Cashmore, 2010). Facebook functions

as a prime example of what Henry Jenkins (2006) calls

"participatory culture," a locus of media convergence

where consumers of media no longer only consume it, but

also act as its producers. Corporations, musicians,

religious organizations, and clubs create Facebook

Pages, while individuals sign up and fill out their

personal profiles. The information that organizations

and people choose to share on Facebook shapes their

online identity. How those Pages and profiles look and

the information they contain is determined by the design

of the software system that supports them. How that

software functions is the result of decisions made by

programmers and leaders within the company behind the

website.

This paper explores how the

technological design of Facebook homogenizes identity

and limits personal representation. I look at how that

homogenization transforms individuals into instruments

of capital, and enforces digital gates that segregate

users along racial boundaries (Watkins, 2009). Using a

software studies methodology that considers the design

of the underlying software system (Manovich, 2008), I

look at how the use of finite lists and links for

personal details limits self-description. In what ways

the system controls one's visual presentation of self

identity is analyzed in terms of its relation to the new

digital economy. I also explore the creative ways that

users resist the limitations Facebook imposes, as well

as theorize how technological changes to the system

could relax its homogenizing and limiting effects.

Methods

The developed world is now fully

integrated into and dependent on computational systems

that rely on software. Most critical writing about new

media fails to explore this underlying layer of the

system (Wardrip-Fruin, 2009). If we are to understand

the effects of these systems, it is imperative that we

investigate the ways that software, through both its

vast potential and its limiting paradigms of thought,

leads to certain kinds of systems and not to others.

Matthew Fuller, in his volume "Software

Studies \ A Lexicon," refers to this balance between

potential and limit as "conditions of possibility."

(Fuller, 2008, p. 2) Just as the principle of linguistic

relativity theorizes that the structure of spoken or

written language affects our ability to think (the

Sapir-Whorf hypothesis) (Hoijer, 1954), so does the

structure of computer languages affect the types of

procedures and algorithms we can create in software.

Given that software now "permeates all areas of

contemporary society," (Manovich, 2008, p. 8) we need to

consider this software within the context of its

inherent limitations (both technical and cultural) as we

investigate the media it enables.

Therefore, in this paper I will utilize

a software studies approach, as outlined by Fuller and

Lev Manovich, in my analysis of how Facebook homogenizes

identity. Consideration will be given to the ways that

the syntactic, economic, and cultural aspects of

software development lead to certain types of

human-computer interfaces. In addition, as part of this

cultural aspect, I will also look at who is

writing today's software, and how their histories lead

to certain types of user experiences.

My viewing of Facebook for this paper

took place between April and May of 2011. As Facebook is

constantly changing the site, features discussed in this

paper may change at a later date.

Literature Review

Software studies is a relatively young

discipline, even for new media scholarship. The term was

first coined by Manovich in The Language of New

Media (2001), but has only come to refer to a

particular methodological approach in the last few

years. The New Media Reader (Wardrip-Fruin

& Montfort, 2003) anthologized papers that explore

the history of software as it relates to cultural

history. Fuller's aforementioned 2008 volume was the

first text published specifically about software

studies. In 2009, Wardrip-Fruin published Expressive

Processing, exploring how software drives

narrative technologies such as games and digital

fiction. This is the first book in a new MIT Press

series on the subject, which is edited by Manovich,

Fuller, and Wardrip-Fruin. The most recent edition in

the series is a work that explores the relationship

between programmability and ideology (Chun, 2011a).

Software studies first focus on the two

most important aspects of software, data structures and

algorithms (Manovich, 2008; Goffey, 2008). How

programmers compose structures to hold data controls the

internal representation of those data stored by the

program, and thus has a significant affect on the way

that data can be searched, presented, or stored. A

fundamental unit of many such structures is the list, a

flexible and "ordered group of entities (Adam, 2008, p.

174)." Algorithms, on the other hand, are abstract

procedures devised by computer scientists to operate on

that data, stipulating how the data flows through the

program, and the methods for evaluating and transforming

it into whatever the program requires (Goffey, 2008).

Other relevant topics within this

paradigm include the relationships between computational

power and social authority (Eglash, 2008), and the ways

that notions of interaction disrupt the composition of

algorithms, forcing modes of action on both the computer

and its human counterparts (Murtaugh, 2008). A number of

scholars have recently explored how race intersects with

technology, including the notion of race as a

technology (Chun, 2011b), the similarities between

physical and digital gated communities (Watkins, 2009),

and how aspects of modularity in UNIX relate to the

structures of racism (McPherson, 2011).

In order to understand how Facebook

homogenizes identity, it is also necessary to understand

previous investigations of identity in network spaces.

In general, identity functions as a "self-concept," or

"the totality of the individual's thoughts and feelings

with reference to himself as an object (Rosenberg, 1979,

p. 8)." Identities are personal "sources of meaning"

based on self-construction and individuation, and within

the network society, organize around one's single

primary identity before they combine to develop into

collective identities (Castells, 1997, p. 6). These

collective identities are supported by information

communication technologies such as mobile phones, social

networks, and electronic messaging systems.

The movement into online spaces, which

started en masse with the launch of Netscape

Navigator in 1995, has had a further broadening

effect on identity. In its infancy, the web was

primarily an anonymous space where anyone could adopt

any identity without others connecting them to their

offline selves. This allowed role-playing as alternative

identities within chat rooms, MUDs, and bulletin boards

(Turkle, 1995). The option to role play in this way led

to a more fully engaged act of identity tourism, where

individuals try on different racial or gender

identities, enabled by the anonymity of the network

(Stone, 1996; Turkle, 1995; Nakamura, 2002). At first

this tourism manifested primarily in text-based

environments, but as technologies improved, evolved to

extend into visual environments and representations,

such as avatars (Nakamura, 2007). While such role

playing holds potential promise for empathy and

expansion of viewpoint (Zhao, Grasmuck, & Martin,

2008; McKenna, Green, & Gleason., 2002; Suler, 2002;

Rosenmann & Safir, 2006), it can also lead to the

reinforcement of stereotypes through the resultant

suppression of gendered or racial discourse (Nakamura,

2002). Part of Facebook’s current popularity originates

from its exclusionary framework; the site’s genesis as a

boutique Ivy League network has led it to enable

segregation along racial lines, and to its domination of

use by upper class educated whites (Watkins, 2009;

Hargittai, 2011).

Not all online identities are

anonymous. Facebook's requirement (and enforcement) of

real identity within their system makes it the locus of

a significant shift away from anonymous online identity.

Zhao (2006) refers to these online real identities as

"nonymous anchored relationships," connections that

exist within the online world but are supported by

non-anonymous connections in the offline world. As Zhao

explains, if the real world results in the presentation

of "masks" that hide certain aspects of self, and the

anonymous online world facilitates the lifting of that

mask for the presentation of one's "true" self, the

nonymous online world is somewhere in the middle,

allowing people to present their "hoped-for possible

selves" (Yurchisin, Watchravesringkan, & McCabe,

2005). Zhao's 2006 study found that Facebook users tend

to stress "group and consumer identities over personally

narrated ones (p. 1816)." Another study explored this

"hoped-for" concept in regards to racial identity, and

also found that users use self-selected or

autophotography to enhance or steer their online

representations (Grasmuck, Martin, & Zhao, 2009).

These nonymous online spaces that use

and reveal actual identities threaten individual's

abilities to shift their online representations over

time. Those newer to the internet (whether because of

age or lack of exposure) are often slow to realize that

the network retains whatever they post online. This

makes individual change and exploration more difficult

due to the perpetual storage and retrievability of the

information they make public (Blanchette & Johnson,

2002; Mayer-Schonberger, 2009).

To date, no software studies-based

analyses have been published about Facebook. Given

Facebook's increasingly powerful position in

contemporary society, it is essential that scholars

begin to unravel the hows and whys behind the site's

functionality. Doing so requires, among others, a

software studies approach if we are to fully understand

its role and power in the network society. Combining

this approach with an analysis of Facebook's role in the

shaping of identity should reveal new insights critical

to understanding how social media function within

digital culture.

Facebook's Ideology of Singular

Identity and the Commodification of the Individual

Before unraveling some specifics

regarding Facebook and identity homogenization, it's

important to understand how and why the site focuses on

nonymous relationships. According to Facebook CEO and

founder Mark Zuckerberg, "having two identities for

yourself is an example of a lack of integrity

(Kirkpatrick, 2010, p. 199)." The design and operation

of Facebook expects and enforces that users will only

craft profiles based on their "real" identities, using

real names and accurate personal details (Facebook,

2011). This ideological position of singular identity

permeates the technological design of Facebook, and is

partially enforced by the culture of transparency the

site promotes. The more one's personal details are

shared with the world, the harder it is to retrieve or

change them without others noticing—and thus being drawn

to the contradictions such changes might create. This is

further enforced by the larger software ecosystem

Facebook exists within, such as search engines, that

index, store, and retain those personal details in

perpetuity (Blanchette et al., 2002).

Why is Zuckerberg so bullish on

singular identity? He says it's to encourage people to

be more authentic, and that the world will be a better

place if everyone shares their information with anyone

(Kirkpatrick, 2010). Given that Facebook's servers are

primarily constituted of data produced by the immaterial

free labor of its members (Terranova, 2000), and that

the monetary value of Facebook is the advertising

usefulness of that data, it's no wonder that Zuckerberg

prefers extreme transparency. The financial future of

his company depends on it. Facebook now delivers more

ads than Yahoo, Microsoft, and Google combined (Lipsman,

2011). The more data they collect the more advertising

dollars they can deposit (Manovich, 2008).

The value of that data is further

enhanced by its connection to real identity, as well as

the way that singular identity encourages the blending

of one's disparate communities into one space. By

disallowing alternative identities and multiple

accounts, Facebook pushes its users to build networks

containing people from their work, family, and friend

communities. This discourages the code-switching

(Watkins, 2009) that happens when people use different

networks for different aspects of their lives, and

instead forces them to consolidate their online (and

offline) identities into a singular representation. It

literally reduces difference by stifling interactions

that might have happened in alternate spaces, but are

now off-limits because of conflicts between social

communities. For example, a user will resist posting

something about their hobby interests because it

conflicts with their work persona. Therefore, this

blending begins to limit personal representation and is

thus a significant step on the road to identity

homogenization. Further, this limiting makes Facebook's

users more useful instruments of capital, as a reduction

of difference means marketing and product development

tasks are easier and less expensive for corporations.

Community Pages and the

Consolidation of Interest

Ever since Facebook opened itself up to

the public in 2006 (abandoning its previous exclusivity

to university students), it has steadily made changes to

the way the site operates. In April of 2010, Facebook

rolled out a new feature they call 'Community Pages.'

Community Pages made it possible for Facebook users to

'like' topics (in addition to specific brands or groups

who had been represented by Fan Pages), by allowing the

creation of pages devoted to these (relatively) abstract

concepts. For example, a user could 'like' hip hop music

by linking their profile to the 'Hiphop' Community Page.

These pages are not run by any one individual, but

simply serve as collection points that gather links to

everyone on the site who lists themselves as liking the

genre.

The way that Community Pages interface

with an individual's profile is significant. Prior to

this change, each Facebook user had a series of text

boxes on their profile where they could describe

themselves. These boxes were labeled, and included

headings such as 'Activities,' 'Interests,' 'Favorite

Music,' 'Favorite TV Shows,' etc.. Users would fill

these boxes with whatever text they desired. While often

what they listed would fit the category (e.g. a list of

TV shows in the TV Shows box), sometimes they would use

them as methods of distinction or resistance (e.g.

saying that they 'don't watch TV' in the TV Shows box).

When Community Pages were introduced,

Facebook used them as a mandatory replacement for the

previously open-ended text boxes. No longer could users

write whatever they wanted in a text box to describe

themselves. Instead they had to "connect" (link) their

interests with Community Pages already in the system.

During the conversion to the new system, users were

offered the chance to convert what they had in their

text boxes into Community Page links, but that option

only worked when pages already existed with descriptions

similar or identical to their own handmade lists.

The result of this change was

significant. The old contents of many users’ text boxes

were wiped out. Those users most affected were those who

had used the text boxes as methods of resistance or

distinction (either by listing information that wasn't

actually related to the stated topic of the box, or by

being unique in how they described the information).

Even those users who had been using the boxes as

Facebook intended found the bulk of their carefully

crafted text deleted forever.

Why would Facebook enact such a change?

There are two reasons, each related to the other and

both related to the commodification of the individual.

First, standardizing and linking everyone's interests to

Community Pages makes it easier to keep track of who

likes what. "By interacting with these interfaces,

[users] are also mapped: data-driven machine learning

algorithms process [their] collective data traces in

order to discover underlying patterns (Chun, 2011a, p.

9)." Second, this standardization makes it all the

easier to sell advertising to corporations interested in

targeting specific groups of people. For example, if an

advertiser wants to reach those who like hip hop music,

under the old system they would have to think of every

label a user might choose to display that interest. This

could include band names, song titles, genre

descriptions, musician names, etc. Under the new system,

all they need is the list of users already mapped as

'liking' the Hiphop Community Page.

Community Pages are also an

illustrative example of how data structures and

computational power lead to certain kinds of interfaces

or modes of presentation. Under an increasing pressure

to monetize the data they store, Facebook looks for ways

to limit difference across the site. In fact, it’s an

imperative given the exponential increases in data

occurring with their current level of growth. As

described above, being able to sell an advertiser a list

of people that like Hiphop is more valuable than asking

them to target specific keywords. Further, enabling

their advertising algorithms to pre-identify potential

targets of advertisements requires a consolidation of

interest and identity—otherwise there's just too much

data to sift through.

How Lists Limit the

Self-Description of Gender

When a prospective user visits

Facebook's homepage to sign up for a new account, they

are asked six preliminary and mandatory questions. Those

questions are: 1) first name, 2) last name, 3) email, 4)

password, 5) birthday, and 6) gender. While above I have

addressed issues related to questions of name and its

relationship to Facebook's ideology of singular

identity, here I want to start by focusing on this

question of gender.

Facebook asks this mandatory question

as follows: "I am:". For an answer, the user is

presented with a drop-down list containing two choices

they can select from: 'Male' or 'Female.' In other

words, a user can say 'I am Male' or 'I am Female.'

There are no choices to add your own description or to

select a catchall alternative such as 'other' (Figure

1).

|

|

| Figure 1: A

screenshot from Facebook showing what type of

gender a user can choose |

These limited choices exclude a set of

people who don't fit within them, namely those who are

transgender. Transgender individuals are uncomfortable

with the labels 'man' or 'woman' for a variety of

reasons, such as "discomfort with role expectations,

being queer, occasional or more-frequent cross-dressing,

permanent cross-dressing and cross-gender living," as

well as those who undergo gender reassignment surgery

(Stryker & Whittle, 2006, p. xi). Someone with a

transgender identity lives that identity as strongly as

a man or a woman, and, while some might choose to

describe that identity as 'male' or 'female,' others

prefer a more complex description. However, Facebook

excludes them from listing that as part of their user

profiles. This exclusion puts Facebook at odds with

other online communities, such as Second Life, where the

portrayal of gender is a function of the way one

constructs their avatar (although identifying as

transgender within Second Life can be fraught with

prejudice and harassment (Brookey & Cannon, 2009)).

If we accept that Facebook's primary

motivation is to monetize its data and to get its

advertisements in front of eyeballs (Lipsman, 2011),

then why do they exclude an entire group from

participating? Wouldn't the accommodation of as many

people as possible best serve their financial interests?

I'll focus on three reasons that lead to this exclusion.

First is that Facebook is a designed

space, and a designed space inherently represents the

ideologies of those who designed it. Despite software's

propensity to hide its actions and origins, this

"invisibly visible" (Chun, 2011a, p. 15) entity is

something that, at its core, is created by humans. In

other words, software is an embodiment of the

philosophies and cultures of its designers and how they

think (McPherson, 2011). While a demographic analysis of

Facebook's programming staff is not available, we know

from more broad analyses that Silicon Valley is

primarily run by white men, with a significant

underrepresentation from white women and racial/ethnic

minorites—especially in positions of mid- and

upper-level management (Shih et al., 2006, Simard et

al., 2008). This analysis holds true in terms of

Facebook's senior leadership; their executive staff is

15% female (with zero women in technical leadership

roles), while their board of directors is 100% male

(Facebook, 2011b,c). An industry that is failing to hire

and/or promote women and minorities is unlikely to be

run by individuals concerned with the politics of

gender. The biases or prejudices that contribute to this

situation, intentionally or not, have manifest

themselves in this question of "I am:."

Second is that an important component

of Facebook's popularity is the way it allows and

encourages its users to form virtual gated communities.

Craig Watkins (2009) explores this topic at length in

chapter four of his book, The Young and the Digital.

He, as well as Esther Hargittai (Hargittai, 2011), have

found that in the United States, lower class and Latino

users frequent MySpace, while upper class, educated

white users prefer Facebook. An important part of that

preference is that white users desire exclusive

communities that keep the "fake" people out. With this

"I am:" question of gender, Facebook launches each

profile with a degree of exclusion, and thus,

potentially leading to its white users seeing Facebook

as "safe" and "private," "simple" and "selective"

(Watkins, 2009). Enabling those with alternative gender

identities to accurately represent themselves on the

site, not to mention foregrounding the issue as part of

a mandatory question on its homepage, would not be

supportive of the selective atmosphere Facebook has

built, and from which it benefits.

Third is that the drop-down list is an

interface paradigm born out of software. The "I am:"

question allows everyone to make a choice, as long as

it's one of the two options already presented. No

accommodation is made for selecting something other than

male or female. A logical human solution to this problem

would be to let everyone provide their own description.

While a majority of people would still likely choose

male/female, or man/woman, those who don't feel they fit

in either of those categories could write their own

description. As computer users, we tend to blindly

accept this kind of interface without regard for its

exclusions; this is one way that software is

contributing to the homogenizing ways we think about and

describe ourselves.

Drop-down lists, or other interface

models that present a list of predetermined choices

(e.g. radio buttons, check boxes) illustrate the way

that new media interfaces are crafted in response to

methods of programming as much, or more so than they are

in response to notions of human-computer interaction.

This crafting starts with how data is represented within

software systems. The most common building block of

software data structures is the list (Adam, 2008), such

as an array (an ordered set of data accessible by

numerical index). Arrays are typically of preset sizes,

and in the case of the "I am:" question, would be of

size two, one index for 'male' and the other for

'female.' The array serves to manage the data during the

computational stage (e.g. waiting for and then grabbing

the data from the user), but must eventually be stored.

Storage occurs within a database, where each user likely

receives a row of their own, and in which gender would

be stored as a single table cell of data. While this

cell could conceivably contain a string of text taken

from the user, it is more useful for Facebook if they

already know what could be in that box.

Knowing ahead of time what genders are

possible, and limiting those possibilities to a known

set enables a number of subsequent software-driven

actions. First, it is easier for Facebook’s search

engines to index user data if they know what the options

are, because searching through a finite list is much

faster than searching through an unending list of custom

personal descriptions. This means that faster searching

algorithms can be devised. Second, it makes it easier to

make comparisons across users. If everyone writes their

own custom descriptions, then every spelling difference,

every text case difference, and every difference of

phrase makes it harder for Facebook to aggregate users

into broader classifications. Aggregation is a useful

tool for improving computational performance, as it

limits data. Perhaps more importantly, aggregation

better serves the needs of their advertisers who want to

quickly and easily target whole classes of potential

consumers.

Language Lists and the

Representation of Racial and Ethnic Identity

If gender identity is limited to two

choices, how does Facebook manage racial and ethnic

identity? There are no specific questions within one's

profile that ask for this kind of information, but there

is a query in direct relationship to it: languages. At

first glance, this question, just a couple below the

gender drop-down, appears to welcome a self-description.

It is listed as "Languages:" followed by an empty

text-box. However, if one starts typing in this box they

will find it quickly attempts to autocomplete what

they’re typing to match a pre-determined list of

languages.

While there are quite a large number of

languages available for autocompletion, many are still

missing. For example, those who speak the Chinese

languages of Min or Gan cannot select their language.

These languages are spoken by 110 million Chinese people

combined. The Ethiopian language of Gallinya, spoken by

8 million people, is also not available. If a user types

Gallinya in the box anyway and hits Enter, the page

refreshes and fails to list that language on their list.

It acts as if they never typed anything at all.

While Facebook will likely continue to

add languages over time, this method of choosing from a

pre-determined list of choices is once again emblematic

of an interface born from the programmatic thinking of

software developers. In this instance, Facebook has

setup a list much larger than the one for gender, but it

is still a finite list. Therefore, while it presents

similar problems to those posed by the gender question,

it also presents additional problems. First, the list

appears to be most exclusionary of non-western languages

(I could not find an official language from North

America or Europe that doesn’t appear). Second, even

when Facebook does have a match for a particular

language, their spellings sometimes differ from those

used by speakers of those languages (e.g. Facebook lists

Kaqchikel, a language spoken by 500,000 Guatemalans, but

doesn’t list its alternate spelling Kaqchiquel).

Finally, many regional dialects of the languages it does

include are not listed.

It is unsurprising that Facebook hasn’t

been able to include all of the world’s languages in its

list. There are so many variations and versions that the

task might be impossible. However, what is important

about the missing languages, spellings, and dialects is

that it illustrates the degree to which Facebook cannot

preprogram the identifiers of racial and ethnic identity

that the world’s population would use to describe

themselves. That they try to anyway, using a limited

choice interface model, ends up revealing their

“lenticular logic,” magnifying the ways that their

abstractions of identity lead to technologies “which

underwrite the covert racism endemic to our times

(McPherson, 2011).” The result, then, is an interface

that reduces, and therefore excludes, difference. By

forcing individuals to choose particular spellings or

dialects, or to not list their language at all, their

identities are homogenized into smaller collections, all

for the goal of making them easier to sort, search, and

advertise to. This obfuscation of identity may enable

some protective benefit, in terms of the way it protects

their real identities from advertisers and others, but

only at the cost of losing the potential for accurate

self-description and the negatives that may entail.

Visual Representation,

Reduction of Difference, and the Digital Economy

Facebook's reduction of difference and

limiting of identity is not restricted to the data it

collects and disseminates, but is also a product of its

visual style. Every user's profile looks nearly

identical, with only a small photograph and a list of

increasingly homogenized identifiers to distinguish

them. Where those elements reside on the page, the

colors they're rendered in, their order of presentation,

and even the background behind them are all

predetermined. Almost zero customization is possible,

leaving each one of Facebook's 500 million users looking

more and more like the residents of a typical gated

community, even though there is a world of difference on

the other side of the screen.

This visual blurring of difference is

a new trend across the Internet, one which Facebook

appears to be leading. In the earlier days of the Web,

individuals created homepages for themselves using the

limited options available to them. Pages had blinking

text, garish colors, low-resolution photographs, and

poor typography. As the production tools used to craft

webpages improved, so did the uniqueness of designs and

personal representations. But in recent years, the use

of Facebook profiles as one's personal space on the

Internet has risen substantially. Because of the fixed

visual design of these spaces, each individual

represented literally looks the same.

Combining this visual homogenization

with the reductions of difference described earlier

blurs the "territory between production and consumption,

work and cultural expression. ... Production and

consumption are reconfigured within the category of free

labor," and "signals the unfolding of a different logic

of value (Terranova, 2000, p. 35)." This new logic is a

digital economy focused on the monetization of the free

and immaterial labor that each user gives to Facebook.

In return, their Facebook profiles increasingly look

like a cross between a resume and a shopping list,

telling the world who they work for and what products

they consume. As Chun writes so eloquently in her new

software studies book Programmed Visions (Chun,

2011a, p. 13):

|

You. Everywhere you turn,

it's all about you—and the future. You, the

produser. Having turned off the boob tube, or

at least added YouTube, you collaborate, you

communicate, you link in, you download, and

you interact. Together, with known, unknown,

or perhaps unknowable others you tweet, you

tag, you review, you buy, and you click,

building global networks, building community,

building databases upon databases of traces.

You are the engine behind new technologies,

freely producing content, freely building the

future, freely exhausting yourself and others.

Empowered. In the cloud. Telling Facebook and

all your "friends" what's on your mind. ...

But, who or what are you?

You are you, and so is everyone else. A

shifter, you both addresses you as

an individual and reduces you to a you like

everyone else. It is also singular and plural,

thus able to call you and everyone else at the

same time. Hey you. Read this. Tellingly, your

home page is no longer that hokey little thing

you created after your first HTML tutorial;

it's a mass-produced template, or even worse,

someone else's home page—Google's, Facebook's,

the New York Times'. You: you and

everyone; you and no one.

|

Chun's you is the

homogenized you. The you represented by a Facebook

profile, the you whose identity is being reduced to a

set of links—links pointing to Pages that enable the

site's advertisers to sell you the latest and greatest

products of late capital.

Ways Users Resist Profile

Limitations

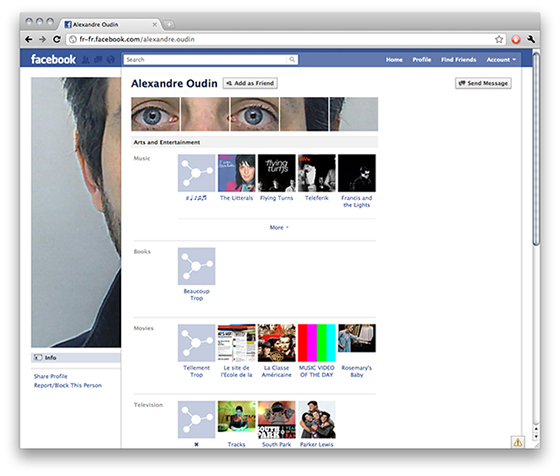

Despite Facebook's reductionist visual

style, some users have found ways to resist it from

within the system. For example, ever since the "new"

profile was released in late 2010, the top of each

profile now includes thumbnails of the last five photos

a user was tagged in. For most, this tends to be a

random collection of event photos, usually without any

particular ordering. A few users, however, utilize their

knowledge of how it works to construct singular images

that stretch across their page from left to right, using

the five photos combined with their profile image as

tiles of a larger image (Figure 2). While this technique

results in a more distinctive visual profile than the

norm, it is still within the larger context of an

extremely confined visual space that is the Facebook

profile. For example, the user in Figure 1 is still

confined to liking pages for movies, books, and other

brands or media represented by Facebook Pages.

|

| Figure 2: An example of a

Facebook profile hack by Alexandre Oudin,

using the last five photos across the top in

conjunction with the profile photo to break

out of the conventional visual style of a

typical profile. |

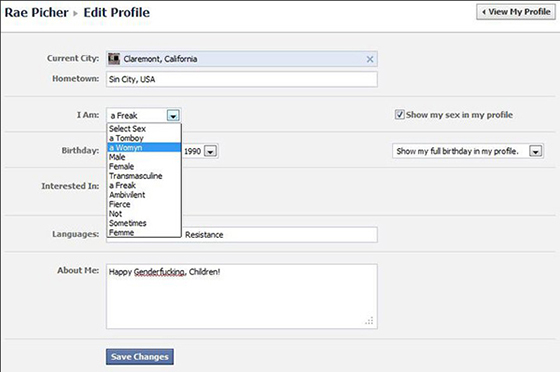

A more significant trend is the action

of gender hacking. Using tools built into the major

browsers for live editing of HTML and CSS, users are

able to temporarily modify the "I am:" gender drop-down

list elements. A video on Facebook (Bayaidah, 2011)

teaches people how to accomplish this (Figure 3). The

technique allows users to add whatever descriptor they

want to the drop-down box (Figure 4), be it

'Transmasculine,' 'Femme,' or 'Fierce' (Picher, 2011).

While the drop-down modifiction will not persist beyond

the first save, the act results in a permanent

alteration of the user's profile; previous and future

additions to their News Feed refer to the user with a

gender-neutral pronoun such as 'their' instead of 'her'

or his.' Technically, this is because users are changing

the data in the 'value' field of each of their drop-down

choices to 0 (1=Female, 2=Male). That the inserted value

of 0 results in a gender-neutral self-description, even

on past entries, clearly shows that Facebook has the

code in place to allow such neutrality—even if they

don't use reveal it in the interface. This is further

evidence that Facebook prefers a limiting of gendered

description even when they've taken the time to program

a system with more options than two.

|

|

Figure 3: A screenshot from

Simon Bayaidah's video on how to hack the

gender drop-down dialog in the Facebook

profile editing interface. Such editing allows

not only a temporary addition to the drop-down

choices, but also triggers Facebook to

automatically use gender-neutral pronouns when

describing the user's actions in their News

Feed.

|

|

|

Figure 4: Rae Picher's example

of gender hacking the Facebook Profile editor

based on the technique outlined by Simon

Bayaidah (Fig. 3). This image was used on her

Facebook note titled Facebook's Gender

Binary Got You Down?

|

Other users take a more exclusionary

approach. Popular options include refusing to list any

personal information beyond the most basic required to

gain the account, using false information to create

profiles that don't adhere to Facebook's real identity

requirement, or avoiding Facebook altogether. While

these three options are resistive in nature, they also

result in a less than full participation within the

economy of Facebook. As the site continues to grow into

a primary communication technology, those who resist in

these ways may be at a distinct disadvantage in areas

such as job search networking or even regular social

interaction.

How Technological Changes Could

Relax Facebook's Homogenization of Identity

Given the degree to which the

homogenization of identity is an essential component of

Facebook's bottom line, it's illogical to presume they

want to reverse the trend. However, to the extent that

some of the conditions described in this paper are

solely the product of programmatic thinking, there is

room for improvement. In particular, any feature of the

site that limits choice could be written to limit choice

less, or to allow nearly unlimited choice. Limits are

ultimately the results of decisions made by programmers

to implement a feature in a specific way. In the cases

of the gender or language questions, for example, the

site could allow users to enter any text they want

without loosing the aggregation characteristics of the

current method. Doing so would require algorithms that

perform pattern matching on those entered texts, looking

for ways to programmatically make the connections

between items that humans so easily do. Alternate

spellings of a specific language could be combined under

one link while still allowing the user to spell it how

they want to. Varied transgender descriptions could

still be collected into a subset of identifiers. Such an

approach might also be limiting of self-description, but

it would be much less so.

Another change that would likely make

a more fundamental difference is an expansion of the

demographics of software developers. As Shih (2006)

points out, the ranks of computer scientists skew

heavily towards white men. While there are certainly

exceptions, white men educated in US engineering schools

tend to have a certain view of the world. Adding people

of various colors and genders to the programming staff

(especially in positions of leadership) would change the

final product because each and every feature we see on

Facebook is the result of a human decision. If we want

our software to be more inclusive of racial, ethnic, and

gendered viewpoints, then we need a broader demographic

bringing their varied contexts to the table when

designing the system and writing their code.

Summary

This paper has shown how Facebook

homogenizes identity and limits personal representation,

all in the service of late capital and to the detriment

of gender, racial, and ethnic minorities. The company

employs its tools of singular identity, limited

self-description, and consistent visual presentation in

order to aggregate its users into reductive chunks of

data. These data describe people not as the complex

social and cultural constructions that they are, but

instead as collections of consumers to be marketed to

and managed. There are many reasons the company has made

these choices, including the demographics of its

software development staff and its capitalistic

imperative to monetize its database. However, to fully

understand how this new digital juggernaut functions it

is important to analyze the core component at the heart

of it: software. Software is built by humans but also

produces new types of thinking that lead to specific

types of interfaces. In the case of Facebook, these

interfaces are taking the vast promise of an

internet-enabled space of tolerance and, in new ways,

imposing age-old practices of discrimination. By

exploring software as part of our larger cultural

history we can begin to envision new ways of thinking

that might help us break away from old ideas in our new

digital culture.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to Lisa Nakamura for

introducing me to much of the theoretical material

underpinning this work. Additional thanks to Lisa as

well as to Kate McDowell for reading and comments on

early drafts.

|

|

Works Cited

Adam, Alison. (2008). Lists. In Fuller,

Matthew (Ed.), Software Studies \ A Lexicon

(pp. 174-178). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Bayaidah, Simon. (2011, July 4). Gender

Neutral (video). Facebook.com. Retrieved from:

http://www.facebook.com/video/video.php?v=549384115767

Blanchette, Jean-Francois & Johnson,

Deborah G. (2002). Data Retention and the Panoptic

Society: The Social Benefits of Forgetfulness. The

Information Society, 18, 33-45.

Brookey, R.A. & Cannon, K.L. (2009).

Sex Lives in Second Life. Critical Studies in Media

Communication 26(2), 145-164.

Cashmore, Pete. (2010, Dec 30). How

Facebook Eclipsed Google in 2010. CNN.com.

Retrieved from http://articles.cnn.com/2010-12-30/tech/facebook.

beats.google.cashmore_1_google-buzz-social-layer-gmail-users

Castells, Manuel. (1997). The Power

of Identity: Information Age, Vol. 2. Malden,

Mass.: Blackwell.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. (2011). Programmed

Visions: Software and Memory. Cambridge, Mass.:

MIT Press.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. (2011). Race

and/as Technology, or How to do Things to Race. In

Nakamura, Lisa & Chow-White, Peter (Eds.), Race

After the Internet. New York: Routledge.

(forthcoming)

Eglash, Ron. (2008). Computing Power. In

Fuller, Matthew (Ed.), Software Studies \ A Lexicon

(pp. 55-63). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Facebook. (2011, May 2). Statement of

Rights and Responsibilities. Facebook.com.

Retrieved from http://www.facebook.com/terms.php.

Facebook. (2011, July 4). Executive Bios.

Facebook.com. Retrieved from http://www.facebook.com/info.php?execbios

Facebook. (2011, July 4). Factsheet. Facebook.com.

Retrieved from http://www.facebook.com/info.php?factsheet

Fuller, Matthew. (2008). Software

Studies \ A Lexicon. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Goffey, Andrew. (2008). Algorithm. In

Fuller, Matthew (Ed.), Software Studies \ A Lexicon

(pp. 21-30). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Grasmuck, S., Martin, J. & Zhao, S.

(2009). Ethno-Racial Identity Displays on Facebook. Journal

of Computer-Mediated Communication 15, 158-188.

Hargittai, Eszter. (2011). Open Doors,

Closed Spaces? Differentiated Adoption of Social network

Sites by User Background. In Nakamura, Lisa &

Chow-White, Peter (Eds.), Race After the Internet.

New York: Routledge. (forthcoming)

Hoijer, Harry. (1954). Language in

culture: Conference on the interrelations of language

and other aspects of culture. Chicago: University

of Chicago Press.

Jenkins, Henry. (2006). Convergence

Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New

York: New York University Press.

Kirkpatrick, David. The Facebook

Effect. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010.

Lipsman, Andrew. (2011, May 4). U.S.

Online Display Advertising Market Delivers 1.1 Trillion

Impressions in Q1 2011. comScore.com.

Retrieved from http://www.comscore.com/Press_Events/Press_Releases/2011/5/U.S._Online_Display_Advertising_Market_Delivers_1.1_Trillion_Impressions_in_Q1_2011

Manovich, Lev. (2001). The Language

of New Media. Cambridge, Mass.:MIT Press.

Manovich, Lev. (2008). Software

Takes Command. softwarestudies.com. Retrieved

from http://softwarestudies.com/softbook/manovich_softbook_11_20_2008.pdf

(draft)

Mayer-Schonberger, Viktor. (2009). Delete:

The Virtue of Forgetting in the Digital Age.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

McKenna, K. Y. A., Green, A. S., &

Gleason, M. E. J. (2002). Relationship formation on the

Internet: What’s the big attraction? Journal of

Social Issues, 58(1), 9–31.

McPherson, Tara. (2011). U.S. Operating

Systems at Midcentury: The Intertwining of Race and

UNIX. In Nakamura, Lisa & Chow-White, Peter (Eds.),

Race After the Internet. New York: Routledge.

(forthcoming)

Murtaugh, Michael. (2008). Interaction.

In Fuller, Matthew (Ed.), Software Studies \ A

Lexicon (pp. 143-148). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT

Press.

Nakamura, Lisa. Cybertypes: Race,

Ethnicity, and Identity on the Internet. New

York: Routledge, 2002.

Nakamura, Lisa. (2007). Digitizing

Race: Visual Cultures of the Internet.

Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Picher, Rae. (2011, July 4). Facebook's

Gender Binary Got You Down? Facebook.com. Retrieved

from: http://www.facebook.com/notes/rae-

picher/facebooks-gender-binary-got-you-down/10150166319923922

Rosenberg, Morris. (1986). Conceiving

the Self. Malabar, FL: Robert E Krieger

Publishing Co.

Rosenmann A. & Safir, M.P., (2006).

Forced online: Push factors of Internet Sexuality: A

preliminary study of online paraphilic empowerment. Journal

of Homosexuality, 51(3), 71-92.

Shih, Johanna. (2006). Circumventing

Discrimination: Gender and Ethnic Strategies in Silicon

Valley. Gender & Society 20(2), 17-206.

Stone, A.A. (1996). The war of

desire and technology at the close of the mechanical

age. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Stryker, Susan & Whittle, Stephen.

(2006). The Transgender Studies Reader. New

York: Routledge.

Suler, J.R. (2002). Identity management

in cyberspace. Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic

Studies, 4(4), 455-459.

Terranova, Tiziana. (2000). Free Labor:

Producing Culture for the Digital Economy. Social

Text 18(2), 33-58.

Turkle, Sherry. (1995) Life on the

screen: Identity in the age of the Internet.

New York: Simon & Schuster.

Wardrip-Fruin, Noah & Montfort, Nick

(Eds.). (2003). The New Media Reader.

Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Wardrip-Fruin, Noah. (2009). Expressive

Processing. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Watkins, Craig. (2009). The Young

and the Digital: What the Migration to Social Network

Sites, Games, and Anytime, Anywhere Media Means for

our Future. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Yurchisin, J., Watchravesringkan, K.

& McCabe, D.B. (2005). An exploration of identity

re-creation in the context of Internet dating. Social

Behavior and Personality, 33(8), 735-750.

Zhao, S., Grasmuck, S., & Martin, J.

(2008). Identity construction on Facebook: Digital

empowerment in anchored relationships. Computers in

Human Behavior 24: 1816-1836.

|

![]() where no other claim is indicated.

where no other claim is indicated.

![]() where no other claim is indicated.

where no other claim is indicated.