Abstract

| Homi K. Bhabha has written that authorized

power in a hybrid culture 'does not depend on the persistence

of tradition; it is resourced by the power of tradition to

be reinscribed through conditions of contingency and contradictoriness…'

(Bhabha, p. 2). This view of culture is one aligned with concepts

of flux and transition. Hybrid cultural identity is created

as time progresses, in part based on contingency. |

|

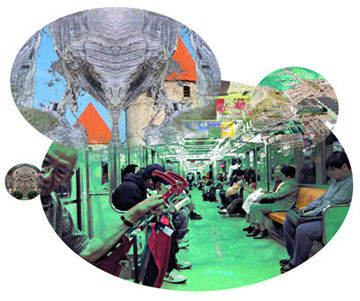

| Image 1: It is said

that green energy pervades Leistavia - the Constitution

contains many proactive conservation measures, in part

based in the 1838 Laws of Pitcairn Island. |

|

The boundaries of hybrid cultures are negotiated

and able to absorb diverse cultural influences: borders are active

sites of intersection and overlap, which support the creation

of in-between identities. Hybrid cultures are antagonistic to

standing authority and cultural hegemony – hybridisation

engenders diversity and heterogeneity, once framed as bastardisation.

Heterogeneity and multiplicity are here underlined as important

aspects of hybrid cultures.

Heterogeneity, multiplicity and rupture are three

aspects of Deleuze and Guattari's rhizome that have been identified

by Stephen Wray as similarly characteristic of the internet. This

makes the internet an entirely suitable place to manufacture a

hybrid cultural identity, with a cultural profile akin to that

reported in mainstream news media. This paper maps out the above

points with reference to the online/internet project the

District of Leistavia welcomes you created by

the author.

Introduction

This paper maps multiplicity, contradictoriness

and contingency within a framework of creative practice that is

sourced in cultural diversity and facilitated largely via the

internet, although inclusive of diverse strategies of presentation.

There are both connections and disconnections between the three

main sections of the paper. Interconnections between the subjects

of hybrid cultures, the internet and Leistavia include aspects

of multiplicity, heterogeneity and rupture. However these three

subjects do not map directly on to each other. Each is discrete.

They overlap at some points however, and these overlaps form the

basis for much of the discussion.

The reader is forewarned that while issues of

culture and identity are among the most important questions that

can be asked, the project that gives the context for this paper

happily acknowledges game playing in cultural structures. Reality

and fiction are not so much blurred as considered to be a dynamic.

Given multiplicity and hierarchical tension are embedded in the

subject matter, the paper also indulges in mode switching as the

various layers of culture, theory, praxis, negotiation, heritage,

trivia, creative license, statistics, profiling, documentation,

referencing and opinion are collated, reflected, incorporated,

explicated, taken apart and reconstructed.

Leistavia

The District of Leistavia is an internet based

hybrid cultural entity. Formative cultural influences are those

of Pitcairn Island, Norfolk Island and Estonia. The reasons for

the selection of these cultures are that the author is descendant

of the first two, and the project was created for exhibition in

Estonia as part of ISEA 2004. This paper looks into issues around

cultural hybridity and the internet, and reveals ways in which

a resultant awareness of processes influenced the creation of

Leistavia. Section one introduces Pitcairn-Norfolk culture in

the context of a discussion of cultural hybridity as its heritage

is not widely known, section two looks at the internet and the

third section examines the project.

Aspects of multiplicity and heterogeneity (which

will be familiar to readers in cultural theory) are underlined

as important to hybrid cultures and the process of hybridisation.

The discussion of hybridity is inclusive, incorporating diverse

theoretical and cultural perspectives. The sense in which hybrid

cultures stand in tension to authority will be discussed in section

one, and this tension is reflected in the writing of the paper.

In examining etymology for example, the Pocket Oxford is quoted

rather than the Oxford Dictionary, and cited material includes

references to Latin/Dutch and Singaporean-Malaysian/English dictionaries.

Hybrid cultures are seen to be situated in-between

cultures, just as Pitcairn-Norfolk is located between Tahitian

and Old English, and Leistavia is placed in-between its three

founding cultures. In being located in-between, hybrids are also

positioned outside parent cultures in the sense that they are

not located entirely within. This in-between location engenders

a diversity that creates a third space of its own authenticity,

and highlights the way in which borders are complex in hybrid

arenas.

While heterogeneity and multiplicity are identified

as important to hybrid cultures, they have also been identified

as applicable to the internet. Section two of this paper turns

to the internet, the facilitation and support mechanism for creating

and maintaining much of Leistavia. In effect, the internet allowed

for an in-between place, where Pitcairn-Norfolk and Estonian cultural

forces were freely interacted and exchanged. It is reasonable

to ask for clarification of the capacity of the internet to allow

such cultural transaction and this leads the paper towards the

concept of the rhizome.

It is now understood that the internet is explainable

within the terms of Deleuze and Guattari's concept of rhizome.

This theme is introduced here by reference to Stephen Wray's paper

Rhizomes, nomads, and resistant internet use which provides

a broad view of writing on the subject. The aspects of the rhizome

that are important to the Leistavia project and therefore this

paper are those of heterogeneity, multiplicity and rupture.

Heterogeneity and multiplicity are common to

both hybrid cultures and the rhizome. A third characteristic of

the rhizome, that of asignifying rupture, will later illuminate

the process of cultural hybridisation in the specific context

of Pitcairn-Norfolk cultural output and heritage. An understanding

of the concept of rupture which underpins explanations of the

process of hybridisation, was utilised in creating the hybrid

internet entity Leistavia. However there is no argument that rupture

is the only means of discussing process in hybrid culture; rather

it is one way. Again, it is the overlap of concepts that is being

referred to.

An awareness of the rhizomatic internet was brought

together with a reading of hybrid cultures, and the combination

formed the rationale for instigating the District of Leistavia

project. Section three looks at the formation of Leistavia, specifically

the constitution voting questions derived from research into the

three formative cultures, and the collated responses to the questions.

Given that a process of rupture could underscore cultural hybridisation,

then it was considered possible to take any two or more cultures

and create a hybrid entity utilising the same processes.

The collated responses are authentic statistics

of actual voter opinions, and are similar to statistics widely

reported in news media regarding issues of the day. Viewpoints

antagonistic to democratic and monetarist political and financial

structures were recorded and are indicative of the Leistavian

community; this result is among a range of outcomes discussed.

The background to formulating the constitution voting questions

is then given prior to the questions themselves with replies expressed

in percentages.

The status of the Leistavian community is imprecise

and ambivalent, partly due to the reality/fiction dynamic. Other

reasons are that hybrid cultures have imprecise and dynamic boundaries,

and are subject to alteration as time progresses. These are facets

of hybrid cultures both online and offline, which will be elaborated

upon in the sections following. The discussion proceeds along

the line of an investigation into the little known characteristics

of the community formed as a consequence of one of the most well

known mutinies in British naval and Tahitian colonial history.

1. Hybrid cultures

and Pitcairn and Norfolk Islands

Pitcairn and Norfolk Islands

A substantial discourse on cultural hybridity

has occurred in cultural theory over the past several years [1].

Much of this discussion is predicated on the locations of hybrid

cultures – in borderland city neighbourhoods [2], at the

border between countries (for example Mexico and the United States

of America [3], as part of the debate framed by post colonialism

and within the debate into the consequences of globalisation.

This paper looks to another context for examining

cultural hybridity: that of Pitcairn-Norfolk culture, established

on Pitcairn Island in 1790 following the mutiny on HMS Bounty.

The reason for the interest in this context is firstly the cultural

affiliation of the writer. Further reasons are that unlike much

debate thus far, the location is neither urban, suburban nor city

but rather two tiny islands separated by thousands of miles of

Pacific Ocean. The formative Pacific cultures are not the consequence

of clashing along a shared border. However, one reading of discourse

on city border-land hybrid situations is the awareness that hybrid

cultures are not simple mergers of two cultures, but instead result

in a so-called 'third space' of their own authenticity. There

is currency here to the subject under review.

Post-colonial debate is often predicated on power

structures of dominant [usually] European culture over indigenous

culture, which is not applicable here, due to historic reasons.

The loss of nearly all adult males (i.e. Polynesian and English)

in early Pitcairn heritage created a situation where dominant

European and customary Polynesian practices were interwoven as

influences. The culture is not the result of a power structure

based on coloniser and oppressed. The role of women (the only

Polynesian survivors) in the first few decades of the culture

exactly at the time it was being established was significant if

not extraordinary.

|

| Image 2: This images

partly shows Thursday October Christian’s house

(son of Fletcher Christian) on Pitcairn Island prior

to being blown down recently. |

|

While globalisation is a relatively recent

phenomenon Pitcairn Island was settled in the late eighteenth

century. Intriguingly, the current population of forty seven

includes eight websites directly arising from the island,

and there is a Friends of Pitcairn mail list that generates

between six and twenty six emails per day. However this may

simply be a function of the necessity for communication to

be facilitated by technology in remote locations. |

Pitcairn is itself quintessentially a story of

globalisation, given the originating desire of the English to

procure breadfruit for slaves in the West Indies, by travelling

to Tahiti to secure the plants. The negative impacts of globalisation

upon small societies are well reported, but are not applicable

in this instance. The uniqueness of the situation necessitates

for the purposes of this discussion a brief outline of Pitcairn

and Norfolk heritage.

In 1788, HMAV Bounty [His Majesty's

Armed Vessel] left England under the naval command of Captain

Bligh, charged with the mission of taking breadfruit plants from

Tahiti to the West Indies. After a protracted stay on Tahiti,

the ship departed in April 1789 shortly after which there was

a mutiny led by Fletcher Christian. After the mutiny, the Bounty

returned to Tahiti to pick up friends and lovers, though it has

been claimed that this was partly by trickery [4]. In December

it was discovered that Pitcairn Island had been incorrectly charted

on maps and the island was found in January 1790, after which

settlement was made.

Within ten years, all but one of the adult males

– six men of Polynesian origin and eight out of nine of

English origin, perished as a result of racial war, murder, insanity

and consumption - Edward Young was the only one to die peacefully,

of asthma (Nicolson, p. 218-221) [5]. Consequently, the remaining

twelve Tahitian adult women were a considerable influence on all

matters in the early years – Pitcairn officially gave women

the vote in 1838.

Considerable research and creative activity around

Pitcairn and Norfolk Islands has already taken place, going back

to the 1930's with Harry Shapiro's now discredited anthropological

studies [6]. The mutiny on the Bounty has been the subject

of four feature films and a musical. Writers are continually adding

to research about the culture, and those of its precedents [7].

Pacific Union College in the USA has a Pitcairn Islands Study

Centre.

However the reading of the culture needs to be

updated. In the first place it is demonstrably a hybrid culture,

though this assertion has not yet been made of Pitcairn-Norfolk.

The use of the hyphenated name is an innovation made here. Most

commentators refer to Pitcairn Island and Norfolk Island as if

they were two separate entities, primarily due to the geographical

separation.

The islands do have differences, the main one

being that Pitcairn Island was converted to Seventh Day Adventism

in the late nineteenth century. Norfolk Islanders are less specific

and strict in observance of religion. There is a pattern of conservatism

and liberalism, Pitcairn and Norfolk respectively, which has been

noted on those rare occasions when Norfolk Islanders have visited

Pitcairn.

However, inhabitants of both islands share DNA.

The language uses the same words. Family names are common. The

reason for the separation was that due to overcrowding, in 1856

all Pitcairners left Pitcairn and settled on Norfolk Island, which

was believed to have been gifted by Queen Victoria. The people

who live on Pitcairn today are descendants of those who left Norfolk

and returned to their birthplace. Most Pitcairn Island descendants

now live on Norfolk Island. As such, the connections between the

two islands run deeper than the factors of separation.

Hybrid cultures

The Pocket Oxford Dictionary (2000, p. 430)

gives the meaning of 'hybrid' as '1 offspring of two plants or

animals of different species or varieties. 2 thing composed of

diverse elements, e.g. a word with parts taken from different

languages.' The root of the term 'hybrid' is the Latin hibrida.

| According to the Wolters' Latin-Dutch

dictionary 'hibrida' means: 'bastard, Child of a Roman and

a foreigner, or of a free person and a slave.' The Grote

van Dale dictionary also first cites this original meaning,

and then adds: 'something that comprises heterogenous elements.'

'Hybridisation' according to the same van Dale is a common

notion in biochemistry (relating to the merging of different

types of DNA). And in the social sciences and philosophy

the concepts of 'hybrid' and 'hybridity' crop up. In 'Krisis

– tijdschrift voor filosophe' hybridity is described

as 'the mixture of elements which are different and which

are generally separate from each other' … On the basis

of a study carried out into the development of Mexican culture

it is stated that this culture, as a melting together of

different 'authentic' cultures, is a typical example of

a hybrid culture – but that at the same time it is

highly authentic. Authenticity and hybridity are not opposites

but are natural extensions of each other. Hybridity produces

new forms of authenticity and is inherent in processes of

social and cultural dynamics in which various cultures confront

each other (Europan 6). |

The above paragraph, from the architectural conference

Europan aptly captures a number of important points about hybridity,

summarising in one instance the words of a number of writers on

the subject. These key elements are those of heterogeneity (diversity

in constitution), multiplicity (mixtures of elements) and unique

authenticity. These are introduced by reference to genetic bastards,

which underscores a theme of antagonism to authority endemic to

hybrid cultures.

Racial diversity on Pitcairn created genetic

hybrids, children of English fathers and Polynesian mothers (none

of the Polynesian men had offspring). The consequent culture that

developed did not continue in accord with solely English or Tahitian

traditions, but took from both and introduced new elements (the

same can be said of Leistavia, with regard to its three formative

cultural influences).

As Nicolson and Clarke [8] report of Pitcairn,

early generations of the culture wore tapa, cooked in hangi, lived

in English styled wooden houses with thatched Tahitian style rooves

and no latches on the doors, transported themselves in Tahitian

canoes, spoke both English and Tahitian and scented their bodies

with the oil of sweet smelling plants. Both sexes had pierced

ears and adorned themselves with flowers (Nicolson, p. 82). Weaving

in Polynesian style continued until the turn of the 20th century,

and until at least the 70's grass skirts were made for the

tourist trade (Ford, p. 87).

While the above paragraph lays out cultural lineage

along the lines of parentage, part of the unique authenticity

of the culture is clearly demonstrated in the Pitcairn Island

Laws of 1838. These Laws among much else gave women the vote,

made education compulsory for both genders, mixed currencies (dollars,

shillings and pence) and laid out the basis for bartering goods.

The worst crime was to kill a cat, white birds were singled out

for protection and there were extensive paragraphs detailing wood

conservation measures and dispute resolution procedures. There

were no laws against theft or assault as these were unknown [9].

None of the Laws described in this paragraph can be related specifically

to Tahitian or Old English practices (though other Laws have traces),

and by the time they were written only women of the Bounty

were alive. They indicate the way in which the culture developed

solutions to problems as they arose. The Laws were an important

influence on Leistavia, in terms of shaping some of the Constitution

voting questions (discussed in section three).

Developmental contingency is not a matter solely

of Pitcairn-Norfolk heritage, but has been identified as a trace

element of hybridity. Homi Bhabha (Bhabha, p. 2) wrote of 'an

ongoing negotiation that seeks to authorize cultural hybridities

that emerge in moments of historical transformation'. Whilst

this passage of historical transformation is perhaps a reference

to the transformation of cultures at shared boundaries in cities,

it is applicable to Pitcairn-Norfolk cultural heritage, where

the transformation had a fixed start date and developed thereafter.

Leistavia is reflexive of this as it has emerged in a sequence

of moments of internet transformation as part of an art work.

Bhabha (Bhabha, p. 2) went on to say that authorized

power is not based on 'the persistence of tradition' but is 'reinscribed

through conditions of contingency and contradictoriness that attend

upon those who are "in the minority". Hybrid cultures

stratify in unique ways, based on contingency rather than tradition.

Contingency and contradictoriness are characteristic even where

'minority' status does not apply. As Roy Sanders (Sanders, p.

274) remarked of Pitcairn after visiting between 1951 and 1953:

| Pitcairn culture then provides a complex

and often paradoxical standard of status measurement…

Social cohesion lies only in kinship bonds and economic

goods. The sea determines the extent of cooperative behaviour.

In order to gain access to food supplies aboard ships, the

islanders, to use their own term 'pull together'. |

Hybridity disturbs traditions, and replaces tradition

with novel solutions. The solution is one that fits the locale.

The speaker's chair of the Papua New Guinea parliament, for example,

is a cross between the one in the British House of Commons and

a traditional orator stool, 'analogous to the kind of hybrid political

system being molded' (O'Connell, citing Vale). Boundaries in hybrid

cultures are not fixed but negotiable.

Diversification engenders a third space, in-between

cultural resources, a space of it's own making and authenticity.

In this in-between place, traces of formative cultures can be

located, but there will always be aspects that are specific to

the hybrid. A very good indication of this is found in George

P Landow's discussion of the creation of a Singaporean/Malaysian

English dictionary.

Landow reports that the editors of The Times-Chambers

Essential English Dictionary worked with five categories

of words – the first was 'Core English' (which already includes

words from other languages such as bungalow and garage). The second

category is for local versions of English – such as the

Singaporean and Malay word airflown (meaning freshly imported,

high quality). The third group of words are those that are not

used in core English – for example sarabat (a strong tasting

ginger drink. Notably for an English language dictionary, this

third category often includes words for which no English word

exists. The last two categories included slang and informal words;

an example is zap (meaning to photocopy). Informal words derived

from other languages include chim (profound) and malu

(shameful). (Landow).

Hybrid cultures being heterogenic engender multiplicities

in cultural structures rather than supporting the simple reinscription

of tradition. On Pitcairn Island, hand carved items are made by

a large percentage of the populace. Many of these items are traceable

to Polynesian practices such as carving 'walking' sticks, fish,

turtles and other local creatures. In 1823 a Bristol shipwright

visited the island and taught new ways to carve [10]. Unfortunately

it is not recorded exactly what this person taught or even who

they were. As well as Polynesian type cultural output, Pitcairn

carving includes book boxes and a carved vase held by a hand.

The origin of these designs is not known, however it is assumed

a similar process to that of 1823 occurred. Pitcairn carving is

a mix of cultural influences while nonetheless being distinctly

Pitcairn. This aspect of Pitcairn cultural output will be discussed

further in the section which follows, where concepts of heterogeneity,

multiplicity and rupture are elaborated upon in a discussion of

the internet.

II. The rhizome and the internet

As remarked in the introduction, Leistavia is

a hybrid cultural internet based entity. It is reasonable to enquire

why it is that the internet might be suitable for such a project,

and the answer may well lie in the fact that heterogeneity and

multiplicity have been identified by Deleuze and Guattari as aspects

of their concept of rhizome, and the rhizome has been found to

be an adequate tool in describing characteristics of the internet.

There is an overlap of characteristics.

Stephen Wray's paper Rhizomes, nomads, and

resistant internet use maps out the concepts of rhizome and

nomad over a background of communication theory writing into the

attributes and condition of cyberspace, hypertext writing and

the internet. Landow's Hyper/Text/Theory and the anthology

Technoscience and Cyberculture edited by Arnowitz, Martinson

and Menser are given lengthy discussion. Wray then turns to Robin

B Hamman's Rhizome@Internet. Using the Internet as an example

of Deleuze and Guattari's 'Rhizome' where Hamman concluded

that 'the Internet is a rhizome' (cited by Wray, p. 11 of 26).

In the introduction to A Thousand Plateaus

Deleuze and Guattari outline the principles of the rhizome. These

are given as being: connection, heterogeneity, multiplicity, asignifying

rupture, cartography and decalcomania. Connection and heterogeneity

are linked by Deleuze and Guattari: ' any point of a rhizome can

be connected to any other' (Deleuze & Guattari, p. 7). This

is different from trees or similar root structures which have

a point that 'fixes an order'. The writers point out that in a

rhizome, 'semiotic chains of every nature are connected to very

diverse modes of coding (biological, political, economic, etc.).'

This capacity to seamlessly traverse codes resides

at the core of the sense in which a rhizome is heterogenic. 'A

rhizome ceaselessly establishes connections between semiotic chains…

a semiotic chain is like a tuber agglomerating very diverse acts,

not only linguistic, but also perceptive, mimetic, gestural, and

cognitive'. In a multiplicity 'There is no unity to serve as a

pivot in the object, or to divide in the subject' (Ibid., p. 8).

The principle of asignifying rupture refers

to the capacity of the rhizome to 'be broken, shattered at a given

spot, but it will start up again on one of it's old lines, or

on new lines'. Asignifying rupture is an important facet of the

rhizome, as the capacity to break apart and reform on old or new

lines is the means by which the processes of territorialisation

and deterritorialisation are enabled: 'Every rhizome contains

lines of segmentarity according to which it is stratified, territorialized,

organized, signified, attributed, etc., as well as lines of deterritorialization

down which it constantly flees'. In discussing the non-relative

attributes of an orchid and a wasp, they write: 'Each of these

becomings brings about the deterritorialization of one term and

the reterritorialization of the other; the two becomings interlink

and form relays in a circulation of intensities pushing deterritorialization

ever further' (Ibid., p. 10).

Cartography and decalcomania are also discussed together by Deleuze

and Guattari. They regard concepts around that of a genetic axis

as a pivot point, and deep structure as 'like a base sequence

that can be broken down' (Ibid., p. 12) hence these cannot be

principles of a rhizome, as they are 'reproducible principles

of tracing'. A rhizome is 'a map and not a tracing…

The orchid does not reproduce a tracing of the wasp, it forms

a map with the wasp, in a rhizome'. A tracing is arbolic while

a map is an open system: 'The map is open and connectable in all

of it's dimensions; it is detachable, reversible, susceptible

to constant modification.'

Heterogeneity, multiplicity and rupture

Heterogeneity, multiplicity and rupture are

the aspects of the rhizomatic internet of interest here, mainly

because heterogeneity and multiplicity have been identified as

relevant to a consideration of hybrid cultures. The aspect of

rupture is here underlined, as it will be contended shortly that

the capacity to break apart and rejoin – rupture in the

sense of Deleuze and Guattari – is coincidentally typical

of hybrid cultures.

Hamman (cited in Wray, p. 11 of 26) writes of

the principles of connection and heterogeneity that 'It has been

demonstrated here that any point on the Internet, that is any

computer, may connect with any other point'. This aspect of the

internet will be familiar to many.

On the subject of multiplicity, Hamman (p. 11 – 12 of 26,

cited in Wray) writes that 'the user's "multiplicity of nerve

fibres" controls the computer's connection… There is

even a further multiplicity present when using the Internet and

that is the multiplicity of light pixels on the computer screen.

Another part of this third principle of rhizomes is that there

are no points or positions, just lines in a rhizome'.

This was written in 1996, and it could be contended that a multiplicity

of nerve fibres and pixels are at the lower end of scales of multiplicities.

The 'controlling multiplicity of nerve fibres' notion comes from

Deleuze and Guattari, and their example of a puppeteer. There

are however multiplicities of personalities, organisations, purposes,

users, identities, cultures, groups, authorities and anarchies

evident on the internet. A better reading of the multiplicity

of the internet is provided in more recent publications such as

Rachel Green's Internet art, where she writes (Green,

p. 8):

| Both everyday and exotic, public and private,

autonomous and commercial, the internet is a chaotic, diverse

and crowded form of contemporary public space. It is hardly

surprising, therefore, to find so many art forms related

to it: web sites, software, broadcast, photography, animation,

radio and email, to name just a few. Moreover, the computer,

fundamental for experiencing internet art, can be both a

channel and a means of production and can take the form

of a laptop, a cellular phone, an office computer –

each with it's own screen, software and capability –

and the experience of the art work changes accordingly. |

The principle of asignifying rupture, the capacity

to break apart and start again on new lines or old ones, is demonstrated

in Hamman's words by 'The Internet or more correctly the computers

on it, can route information around trouble spots' (Wray, page

12 of 26).

Hamman is here referring to the originating impulse

in creating the internet so that military-industrial data could

withstand nuclear holocaust. He also gives the example of users

in Europe being excluded from access to certain Usenet groups

by a service provider. However a way around the issue was found

within a few hours. All users were required to do was log into

their usual service provider and then on to a third party service

which allowed viewing of the contentious material. (Hamman).

These points can perhaps be added to, given the

benefit of several more years of internet usage. Logging into

the internet from diverse points – making connections from

home, cafes or work then disconnecting and reconnecting later

from a different address – is part of daily life. As many

people will be aware, it is now possible to access online resources

including email from any country with internet access, and in-between

national borders such as departure and arrival lounges in airports.

Such are the smaller details of this particular subject. It is

a point that can be scaled up to one of examining cultural flow.

Whilst heterogeneity and multiplicity were discussed

in regard to hybrid cultures and Pitcairn-Norfolk, it remains

now to discuss asignifying rupture in terms of hybridity. The

argument here is not that hybrid cultures are analogous to rhizomes

or rupture in the sense of both having a limited number of shared

features, but that the articulation of energy flow in hybrid cultures

can be characterised in one sense by rupture. There are a range

of cultural flows coursing through hybrid cultures, of which a

process that mimics rupture is but one.

When a culture absorbs an influence, a break

with the past is made. On Pitcairn, when the method of making

a vase held by the hand was taught, a break with tradition occurred,

a break away from Polynesian roots. However, when such a vase

is made today, a reconnection with Pitcairn tradition takes place.

This would be true of the range of cultural outputs on Pitcairn.

Similarly when the Laws of 1838 were composed, traces of English

or Tahitian culture that were incorporated followed old lines,

while aspects unique to Pitcairn followed new lines.

Disconnection and reconnection in the tangled

membrane of society, is a process that well describes the means

by which a hybrid culture absorbs external cultural influences.

Deleuze and Guattari write of disconnection and reconnection engendering

rhizomic and arbolic states of systems as deterritorialisation

and territorialisation. They introduce these concepts within the

context of discussing asignifying rupture.

It is interesting to relate the whole episode

of the Bounty saga from leaving England to settling on

Pitcairn Island, in terms of territorialisation and deterritorialisation.

Firstly, the sailors are territorialised in their local territory

– at home. They become deterritorialised by boarding the

ship. As Naval company, they are then reterritorialised in a new

hierarchy. On arrival in Tahiti, they became deterritorialised

with extra-ordinary effect (ship's biscuit is replaced by feasting

for example). Staying longer than intended, they entered into

the condition of being territorialised on Tahiti.

Called back on board, their Tahiti life is deterritorialised

and once again they become territorialised in a Naval hierarchy.

Soon after, the sailors mutiny, and put Bligh to sea – literally

a deterritorialisation. The Bounty is deterritorialised

as a ship in His Majesty's Navy. When Tahitian lovers and friends

are taken on board, a dramatic reterritorialisation occurs (both

genders living on a previously Naval vessel). It is discovered

that Pitcairn Island has become deterritorialised – i.e.

mis-charted on maps. On locating the island, the ship becomes

totally deterritorialised (i.e. burnt) and Pitcairn Island is

territorialised [11].

The description given above relies heavily on

the states of becoming territorialised and deterritorialised.

But perhaps a more adequate picture of the intensity and dynamism

of energy at sea and on land, leading up to the mutiny is provided.

The sense in which tradition is broken and re-linked, giving rise

to a reinvigorated new condition that leads to further development

is conveyed better than many current observances of what occurred.

The above description certainly stands in contrast to the standard

description of Bounty events i.e. in 1789, there was a mutiny

aboard HMS Bounty led by Fletcher Christian against Captain

William Bligh who was set to sea in a long boat and sailed across

the Pacific to Indonesia, and the mutineers settled on Pitcairn

Island.

The internet and hybrid culture

The capacity of the internet and hybrid cultures

to be broken apart or shattered and to start again on new or old

lines provides an appropriate context for utilising the internet

to create hybrid cultures composed of diverse formative influences.

In the District of Leistavia, Pitcairn Island, Norfolk Island

and Estonian cultural, political and social influences became

the context for generating a new cultural space.

|

| Image 3: This image

features 'Fat Marguerita' one of the gates to old Tallinn.

Articles from the Estonian Constitution were incorporated

into the Leistavian Constitution, particularly where

these aligned with constitution voting response data.

|

|

Some aspects of the formative cultures become

parts of the generated culture – in this case the territorialisation

follows old lines. Some aspects of Leistavia are not part

of Pitcairn-Norfolk culture (for example some aspects of Leistavia

are derived solely from Estonian influence), and in that context

the reterritorialisation follows new lines. |

The process of collating internet based research

(and providing active links back to original material) and creating

the website for the District of Leistavia project, replicates

asignifying rupture well. For example, parts of the Estonian constitution

were copied from the source website and pasted into Dreamweaver,

where it was formatted appropriately and uploaded to the internet.

In other words, a deterritorialisation of Estonian heritage content

was made and this was territorialised in a web space known as

the District of Leistavia; both places share the right to self

realisation, with the Estonian constitution as the origin. The

territorialisation involved collating material from the geographically

and culturally diverse Pitcairn and Norfolk islands, and putting

these together with Estonian content in the internet territory

of Leistavia.

III. the District of Leistavia welcomes

you

The borders of the District of Leistavia are

digital files. In order to create boundaries, some form of constitution

was required. This necessitated the generation of questions that

could capture information relevant to Leistavia. As such, the

constitution voting questions were written following interconnections

found between the founding cultures. To be specific on this point,

the founding cultural influences on Leistavia are recorded as

bias in the constitution voting questionnaire. Any questionnaire

has cultural bias, and the voting questions have apparent influences

derived from issues of great concern to all three locations, in

particular issues around sovereignty and a critique of Western

European cultural and financial imperialism.

This critique is shared by many beyond the bounds

of Leistavia. One of the peculiarities of the project is that

while 'Leistavia' has an identity, it appears to be a fiction,

yet the voting that formed the basis of the constitution directly

records the actual opinions of those voting.

A research period occurred at the same time as

discussions via email and the internet commenced. The aim was

to locate topics of importance to the three formative locations.

Given the benefit of hindsight, the issues around this process

can now be articulated with some clarity.

It became clear while working on the project

that a singularity in expression was inappropriate to a multiplicity.

Consequently the exhibited project did not consist solely of a

website. The website and questionnaire was augmented by an animated

loop of images and associated documentation and research for the

website, a DVD of images of Leistavia, vinyl prints of the Leistavian

crest and language-equations, hard copy prints, leis and an old

ladder from the Tallinn hospital. The context for the ladder was

that a sense of old architecture was common to all three sources,

and a ladder in architectural terms occupies the space in-between

planes. This was the multiplicity displayed in Estonia as part

of ISEA 2004, that was both 'about' Leistavia and was a multiplicity

of the meanings of the notion of 'Leistavia'.

The third section of this paper examines the

development and creation of the District of Leistavia. Firstly

the collated responses to voting questions are summarised, which

provide an interesting view of the opinions of the participants

in a created hybrid culture - the summary mimics statistics reported

in news media when presenting information around political and

other issues. The research behind the writing of the constitution

questions is then exposed, and the full list of questions and

collated responses for each category is given. Finally, the paper

concludes with a brief commentary on results.

Collated voting responses

Voting closed on the final day of exhibition

in Tallinn, Estonia. Responses were input to Excel so that percentage

statistics could be generated. The results of voting generated

some interesting responses.

For example, the openness of cultural borders

is contentious in Europe where immigration is concerned, and also

in the South Pacific where for example in Fiji the indigenous

people have been attempting to maintain control of the government

in the face of an expanding Fijian-Indian population. However

in voting for the constitution of Leistavia, a substantial majority

of respondents (73%) were in favour of keeping cultural borders

open.

Similarly, it was considered prior to voting

that a degree of sympathy toward the rights of indigenous people

might result in a number of respondents being in favour of special

rights for some groups. However just over three quarters of voters

selected the option of equal rights for all.

The twinning of democracy and monetarist economy

were not favoured by respondents, with only 9% of voters opting

for a democracy and a mere 5% selecting cash based on gold as

the core economic system. The largest percentages of votes (59%)

were given to meritocracy as means for selecting the Head of State

(the person who has served the community best is selected). Nonarchy

(no head of state) received a respectable 30% of votes. The economic

system most highly favoured, with over 60% of votes, was ecologically

sustainable value. Barter was favoured by 20% of voters and spiritual

worth by 14%.

There was a more even spread of votes in the

question that asked voters to select species or sub-categories

for special protection. While the largest percentage opted for

trees and plants (40%), birds, animals and insects received 15,

14 and 10 percent respectively. Primates and aliens received about

the same (seven and six percent respectively) with eight percent

selecting fish.

Clearly the worst digital crime is government/CIA

monitoring of email – this category was selected by 44%

of voters. SPAM was next worst, with 26% of votes, followed closely

by webcam sites that invade privacy at 19%. Lying about your identity

online was not considered a serious crime with only 2% selecting

that option. Given the multiplicity of identity allowed by internet

identity regimes, on reflection this is perhaps not surprising,

but rather a recognition that multiplicity in some identity situations

is acceptable.

Respondents were asked to indicate a preference

for energy source. One reason for the reply options was to gauge

the degree of idealism of the respondents, given that many came

upon the voting form in the context of art. A reasonable degree

of idealism appears to pervade Leistavia, with Ideas selected

by 43% and one fifth of voters selecting Love, as the energy source.

The overwhelming majority of respondents by the

huge margin of 91% in favour, 9% against believed all genders

should have equal rights in law, endorsing world wide moves to

grant gay and lesbian couples the same rights as married heterosexuals.

Intercultural connections and writing

the constitutional voting questions

Whilst it would have been possible to take a

dictatorial or monarchical stance and dictate a constitution (which

has been the strategy for the formation of several internet based

cultures known as micronations) [12], questions of legitimacy

around this approach arose, partly because research revealed that

issues of sovereignty were common to all three formative locations.

It was decided to offer alternate types of constitution as options

on the voting form.

On Norfolk Island, there has been an ongoing

dispute around control of the island and whether or not Australia

legitimately has authority there. There is strong resentment at

central Australian government imposed initiatives, and the

Norfolk Island Self Determination Vanguard

lists issues and invites action. Lawyers for some Pitcairn

Island men have a case before the Privy Council in regard to whether

British Law formally holds over Pitcairn [13]. In Estonia, issues

of sovereignty gave rise to a massive political movement [14]

in the late 1980's and early 1990's such that secession from Russia

was achieved in a bloodless coup with a shadow Estonian government

able to step into power relatively swiftly.

Another interconnection found between Estonian,

Pitcairn and Norfolk culture that was that the borders of all

three have been open to cultural influence and diversity. This

has already been discussed in regard to Pitcairn Island cultural

practice. As Kalevi Kull wrote

Estonia is a border state in the deepest

sense of the word. It has accumulated transition areas of

many types of nature and culture, and therefore the concentration

of different borders in Estonia is higher than in most other

places in the world.

|

Kylli Mariste (an Estonian who became a collaborator

on the project), listed [personal communication] DNA similarities

with Latvia and Lithuania, and historical transgressions of borders

by Germany, Russia, Sweden and Denmark as all having influence

on Estonia. Norfolk Island cultural output forms a diversity without

specific roots, with immigrants such as writer Colleen McCulloch

among those who have settled there, the souvenir trade, public

and independent museums, photographic archives, and a recent reinvigoration

of interest in Polynesian forms with businesses such as design

label Noa Noa. Question 1 of the voting form reflects the issue

of the openness of borders.

Issues recorded in various discussions that arose

out of considering the constitution included whether all nationalities

should have equal rights, i.e. given there is a world wide concern

over the rights of indigenous people, should specific nationalities

have preferential rights over others? A certain cynicism regarding

democracy, power and money, the influence of organisations such

as the International Monetary Fund, and the control exerted by

large countries over smaller ones, were registered in the setting

of the tone of some reply options - see questions 2, 3 and 4 of

the voting form. This cynicism is recorded in contemporary discussions

in Estonia around the virtues or otherwise of commercialism following

the collapse of Soviet control.

A further located interconnection involved trees.

The Norfolk Island flag features a Norfolk pine, for which the

island is internationally known; when Mariste was asked for a

cultural cliché of Estonia she replied with the vision

of a lone tree against a background of sea and sky. The use of

wood resource on Pitcairn Island understandably was spelt out

in detail in the 1838 Laws, as already mentioned. That is to say,

trees and green energy were felt to pervade all three locations.

The 1838 Pitcairn Island Laws also provided penalties for harming

some sub species (cats and white birds as remarked earlier), and

this was used as the context for voting question 5.

For several reasons, question 6 registered the

relevance of the digital to Leistavia. These were firstly that

the borders of Leistavia were digital. Secondly that primary contact

with Estonia was via email and aspects of the culture, history

and constitution of Estonia were freely available on the internet

[15], in English. Thirdly the Friends of Pitcairn Yahoo.com email

list generates huge amounts of email given that the core subject

of life on the island revolves around just 47 inhabitants. Fourthly

the Norfolk Island forum and direct email contact was used as

the basis for discussion of Norfolk Island issues.

The context for question 7 (energy source) reflected

worldwide discussion of ecology, the cultural interconnection

around trees and arose as an issue in research and email conversation

(as well as the previously mentioned query regarding idealistic

tendencies).

The constitution of Estonia, written in 1992,

recognises the right to self-realisation. Question 8 concerned

sexuality – the contentiousness of recognising gay and lesbian

rights in San Francisco and by Anglican and Roman Catholic Churches,

were international news at the time of creating the project.

Constitution of Leistavia voting form

questions and results

| Drop down boxes were used so that online

participants could select appropriate options, or tick boxes

were used to select preferences. The questions are given as

they were presented online during the voting period, with

some additional information edited out as not of relevance

here. |

|

| Image 4: Data visualisation

of responses to the question ‘How is the Head

of State decided?’ Relative sizes are determined

by percentage voting responses, and there are overlaps

and in between parts to the image. |

|

CONSTITUTION OF LEISTAVIA VOTING FORM:

1. In keeping with the founding cultures of Leistavia,

currently the borders are open to outside cultural influence.

Should the borders stay open? Select Yes or No from the drop down

box.

Yes 77.3%.

No 22.7%.

2. Should all nationalities have equal rights?

Answer Yes if all are equal, or No if indigenous rights should

be different.

Yes 76.7%.

No 23.3%.

3. How is the Head of State decided? {Select

one by ticking your choice}.

Democracy - a millionaire is elected by vote. 9%.

Monarchy - the richest family wins forever. 2%.

Meritocracy - the person who has served the community best is

elected. 59%.

Nonarchy - there is no Head of State. 30%.

4. Economic system {select one}.

Barter. 20%.

Cash based on gold. 5%.

Ecologically sustainable value. 61%.

Spiritual worth. 14%.

5. Select two species to be protected {select

two}.

Insects. 10%.

Animals/cats/dogs/wild animals. 14%.

Fish. 8%.

Birds. 15%.

Primates. 7%.

Aliens. 6%.

Trees/plants. 40%.

6. What is the worst digital crime? {Select one}.

Lying about your identity online. 2%.

Slow download times. 9%.

SPAM. 26%.

Webcam sites that invade privacy. 19%.

Governments/CIA monitoring email. 44%.

7. Select the energy source for Leistavia {select

one}.

Electricity/wood/oil/gas/coal. 7%.

Love. 20%.

Intellectual energy/the energy of ideas. 43%.

Random forces of nature. 27%.

Random forces of humans. 2%.

8. Should all genders (female, male, inter) and

sexual orientations be equal in Law? Select Yes or No.

Yes 91%.

No 9%.

Commentary

Perhaps the most surprising results from voting

are (a) the significant rejection of democracy (91% of voters

selected other options) as the basis for a system of government

and (b) the overwhelming preference for meritocracy. While the

ambivalent status of Leistavia perhaps gives rise to caution,

the percentages are large enough to be considered indicative of

a trend that is real. Certainly the status of these statistics

is similar to those reported in news media (television, radio,

newspapers and websites) about contemporary issues.

There is an assumption among Western leaders

that democracy is the only coherent choice for proper governance

of the people. However the results here show that sections of

the art community and those that have an interest in the formation

of virtual communities, are not inclined to agree as a matter

of course. Indeed the presumptive base of the superiority of democracy

has not itself been tested, and it would be very interesting to

allow voters worldwide the opportunity to select between meritocracy

and democracy as proposed bases for governance.

Similarly, there is a presumption that it is

natural to value the dollar in economies and this forms the basis

for internal government policies worldwide and international intervention

in economies by organisations such as the World Bank and the International

Monetary Fund. Results of voting here indicate that at least a

significant proportion of people might wish this presumption reviewed,

and given sustainability was an option, might well prefer it even

where this might mean increased costs to the country/ies involved.

The profile of voters who contributed to the

Constitution of Leistavia is contemporary in flavour. Leistavia

is a place where cultural borders are open, all nationalities

have equal rights, trees and birds are protected, and the monitoring

of email by governments is considered worse than SPAM, webcam

sites that invade privacy and lying about your identity online.

The energy of ideas is greatly respected, and gender and sexual

orientations are equal in law. These are the ideals of a networked,

international and internationally minded group of voters –

a demographic that will play a more significant role in world

culture and politics as time progresses. The project in one sense

has become litmus of the new global person: internet enabled,

politically concerned and ecologically aware. Evidence of this

person can be seen in the global response by people, rather than

politics, to the Tsunami disaster. As the District of Leistavia

traverses 21st century artistic and cultural practice, further

projects are anticipated to arise in new contexts.

|